Texas Native Plants by Region: Complete Restoration Guide

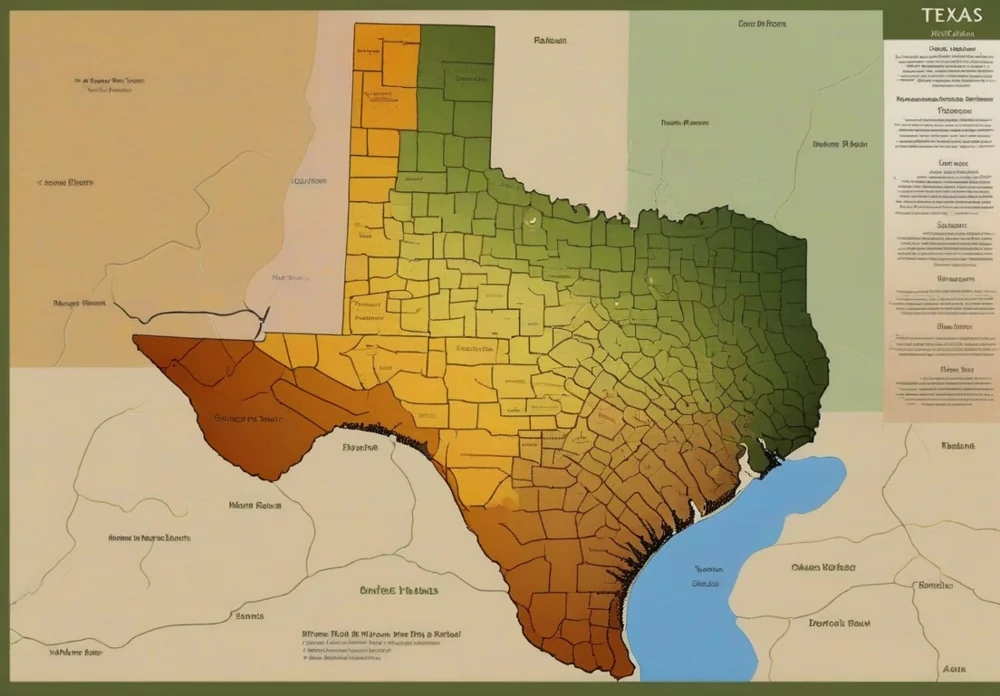

Texas contains an extraordinary tapestry of ecological diversity. From the humid pine forests of the east to the arid desert mountains of the west, from coastal salt marshes to High Plains grasslands, our state encompasses ten distinct ecoregions—each with its own unique climate, soil, and native plant communities. This remarkable variety means that a plant thriving in Houston’s Gulf Coast prairies might struggle in El Paso’s Chihuahuan Desert, just as a Hill Country limestone specialist would fail in East Texas’s acidic soils.

Yet despite this incredible natural heritage, most Texans face a common problem: they don’t know which native plants actually grow in their specific region. Garden centers stock generic ornamentals bred for national markets. Online plant lists overwhelm with hundreds of species but provide little guidance on what belongs where. The result? Well-intentioned landowners plant natives from the wrong ecoregion, leading to failure, frustration, and wasted resources.

This guide solves that problem. Whether you’re restoring prairie on rural acreage, converting your suburban lawn to native landscaping, or simply want to support local wildlife, you’ll find everything you need here: identification of your ecoregion, comprehensive plant lists tailored to your region, step-by-step restoration methods, reliable sourcing information, and seasonal timing calendars.

Understanding Texas Ecoregions

What Are Ecoregions?

Ecoregions are geographic areas characterized by similar climate, geology, soils, vegetation, and wildlife. In Texas, ecoregions represent distinct ecological communities that have developed over thousands of years, shaped by rainfall patterns, temperature extremes, soil types, and natural disturbance cycles like fire and flooding.

Unlike USDA hardiness zones—which indicate only minimum winter temperatures—ecoregions capture the complete ecological picture. Two locations in USDA Zone 8 might have wildly different rainfall, soil pH, and native plant communities. The Piney Woods and Trans-Pecos both include areas in Zone 8, yet one receives 50 inches of rain annually while the other gets just 10 inches. Ecoregions account for these critical differences.

Understanding your ecoregion matters because native plants have evolved specific adaptations to their home region’s conditions. A Blackland Prairie forb has developed tolerance for heavy clay soils and summer drought. A Piney Woods wildflower requires acidic soil and consistent moisture. Planting species adapted to your ecoregion’s specific conditions dramatically increases success rates while reducing maintenance, irrigation needs, and pest problems.

How to Identify Your Ecoregion

Finding your specific ecoregion takes just a few simple steps:

- Check your county location: Use the interactive Texas Parks & Wildlife ecoregion map at tpwd.texas.gov. Enter your county to see which ecoregion you’re in. Many counties span multiple ecoregions, so refine your location further.

- Observe existing vegetation: Look at remnant natural areas, roadsides, and undisturbed patches near you. Do you see dense forests, open grasslands, desert scrub, or oak savanna? This provides immediate clues to your ecoregion.

- Check your soil type: Dig down six inches and examine the soil. Is it sandy, heavy clay, rocky and thin, or dark and loamy? Access the USDA Web Soil Survey for detailed soil information by address.

- Note your annual rainfall: Compare your typical yearly precipitation to the ranges in the ecoregion overview. Rainfall is one of the strongest ecoregion indicators.

- Consider elevation and geography: Are you near the coast, in rolling hills, on flat plains, or in mountains? Topography correlates strongly with ecoregions.

Keep in mind that transition zones exist between ecoregions. If you’re on a boundary, you may successfully grow plants from both adjacent regions. When in doubt, choose plants with the widest natural distribution or consult your local Native Plant Society chapter for guidance.

Texas’s 10 Ecoregions at a Glance

Texas is divided into ten major ecoregions, each with distinct characteristics:

| Ecoregion | Location | Annual Rainfall | Growing Season | Primary Vegetation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piney Woods | Far East Texas | 40-58 inches | 240-280 days | Pine-hardwood forests |

| Gulf Coast Prairies & Marshes | Coastal region | 30-50 inches | 280-320 days | Coastal prairie, salt marsh |

| Post Oak Savannah | East-Central Texas | 30-45 inches | 240-280 days | Oak savanna, grassland |

| Blackland Prairie | North-Central Texas | 30-40 inches | 220-260 days | Tallgrass prairie |

| Cross Timbers | North-Central Texas | 25-35 inches | 220-240 days | Oak woodland, prairie |

| South Texas Plains | South Texas | 20-30 inches | 300-340 days | Thornscrub, grassland |

| Edwards Plateau | Central Texas | 15-33 inches | 240-270 days | Juniper-oak savanna |

| Llano Uplift | Central Texas | 25-30 inches | 230-260 days | Granite outcrop, oak woodland |

| Rolling Plains | West-Central Texas | 20-30 inches | 210-230 days | Mixed-grass prairie |

| High Plains | Panhandle | 15-22 inches | 180-210 days | Shortgrass prairie |

| Trans-Pecos | Far West Texas | 8-16 inches | 180-240 days | Chihuahuan Desert |

Brief Ecoregion Descriptions

Piney Woods blankets 43 counties in far eastern Texas with dense forests of shortleaf, loblolly, and longleaf pine mixed with oaks, sweetgum, and magnolia. Major cities include Texarkana, Tyler, and Nacogdoches.

Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes stretch along the coast from Louisiana to Mexico, including Houston, Corpus Christi, and Galveston. Salt marshes, coastal prairie, and live oak mottes create critical habitat for migrating birds.

Post Oak Savannah forms a transitional zone between eastern forests and central prairies. This region includes College Station and parts of Austin.

Blackland Prairie encompasses the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. Named for its heavy, black clay soils, less than 1% of original prairie remains.

Cross Timbers features alternating bands of oak woodland and grassland running north-south through north-central Texas.

South Texas Plains dominates south Texas from San Antonio to the Rio Grande Valley. Dense, thorny shrubland creates critical wildlife corridors for endangered ocelots.

Edwards Plateau forms the Texas Hill Country around Austin, San Antonio, and Kerrville. Shallow, rocky limestone soils support juniper-oak woodlands.

Llano Uplift appears as a distinct granite dome in Central Texas. Unique granite outcrops support plant species found nowhere else in the state.

Rolling Plains extend across west-central Texas with gently rolling terrain and mesquite-grassland.

High Plains occupy the Panhandle region including Amarillo and Lubbock. Flat topography and low rainfall create classic shortgrass prairie.

Trans-Pecos encompasses far west Texas including El Paso and Big Bend. This Chihuahuan Desert region features extreme aridity and desert-adapted plants.

Why Choose Native Plants for Restoration

KEY TAKEAWAY: Native plants require 70% less water, provide essential food for pollinators, and prevent erosion far better than non-native alternatives. They have evolved over thousands of years to thrive in Texas conditions.

Ecological Benefits

Native plants provide irreplaceable ecological value that non-native species simply cannot match. Research consistently demonstrates that native plants support three to five times more insect biodiversity than non-native ornamentals. This matters because insects form the foundation of food webs—birds need caterpillars to raise nestlings, and most require thousands of caterpillars per nesting season.

A chickadee searching your yard finds abundant food on native oaks (which host over 500 caterpillar species) but virtually nothing on commonly planted Bradford pears or crape myrtles.

Water conservation represents another critical benefit. Native plants develop extensive root systems—often reaching 8 to 15 feet deep—that access groundwater, prevent erosion, and recharge aquifers. A native prairie’s roots can extend two to three times deeper than the above-ground vegetation stands tall. These deep roots reduce stormwater runoff by up to 80% compared to shallow-rooted turf grass.

Soil health improves dramatically with native plantings. As roots grow, die back, and regrow through seasons, they create channels for water infiltration and air circulation while building organic matter. Native prairies can accumulate several inches of rich topsoil per century.

Carbon sequestration in native prairie root systems rivals that of forests. Deep-rooted native grasses store carbon underground where it can remain stable for centuries. Research shows that restoring native grasslands sequesters 1 to 3 tons of carbon per acre annually.

Pollinator support has become critical as bee and butterfly populations decline. Native plants provide nectar and pollen throughout the growing season, plus essential host plants for butterfly and moth larvae. Monarch butterflies require native milkweeds—they cannot complete their lifecycle on any other plant.

Practical Benefits for Landowners

Lower maintenance costs emerge within two to three years of establishment. Native plantings require no fertilizer—in fact, fertilizer often harms natives by encouraging weed competition. Mowing needs drop from weekly to once or twice annually (or eliminated entirely).

Drought tolerance becomes apparent after establishment. Once roots extend deep into the soil profile—typically by the second or third year—native plants survive extended drought without supplemental irrigation. During the severe 2011 Texas drought, established native plantings sailed through months without rain.

Cost savings compound over time. Traditional turf grass costs $2,000 to $3,000 annually per acre for mowing, irrigation, fertilizer, and herbicide, totaling $10,000 to $15,000 over five years. A seed-based native prairie costs $500 to $1,500 in year one, then under $200 annually for spot maintenance, totaling roughly $2,500 over five years.

Property values increasingly reflect native landscaping. As water costs rise and environmental awareness grows, buyers seek low-maintenance, sustainable properties. Several real estate studies document premium prices for properties with mature native landscaping.

Texas Wildlife Tax Exemption

Many Texas landowners can qualify for agricultural valuation (ag exemption) through wildlife management, with native plant restoration as a key component. This property tax benefit can save thousands of dollars annually.

The Texas wildlife tax exemption allows landowners with at least 10 acres (5 acres in some counties) to qualify for agricultural valuation by actively managing wildlife habitat. Habitat control—the most common category—includes activities like native prairie restoration, brush management, wetland restoration, and prescribed burning.

Native plant restoration makes wildlife management practical and straightforward. Unlike some management activities that require ongoing effort and expense, established native plantings provide permanent habitat improvement that satisfies requirements year after year with minimal maintenance.

Native Plant Restoration: Complete Step-by-Step Process

Restoration is a process, not an event. Success requires patience, planning, and realistic expectations. The transformation from degraded land to thriving native ecosystem unfolds over years, not weeks. Understanding this timeline prevents frustration and premature declarations of failure. Your first year will look rough—weedy, sparse, and underwhelming. By year three, you’ll have a stunning, low-maintenance landscape that improves with each passing season.

Step 1: Site Assessment and Analysis

Begin with thorough site analysis. Walk your property and document conditions systematically. Understanding what you have determines what you can do.

Soil testing provides essential baseline information. Collect samples from multiple locations, mixing them together for a composite sample representing the area. Take samples 4 to 6 inches deep. Most county extension offices offer inexpensive soil testing (around $10-$20) that measures pH, texture, major nutrients, and organic matter. Clay content particularly matters—heavy clays require different management than sandy soils.

Sun exposure mapping identifies full sun (6+ hours direct sun daily), partial shade (3-6 hours), and full shade (under 3 hours) areas. Observe throughout the day, noting which sections receive morning versus afternoon sun. Sun patterns change with seasons—what’s sunny in winter may be shaded by deciduous trees in summer.

Existing vegetation inventory separates keepers from removals. Identify native species worth preserving—mature native trees, remnant prairie plants, established native shrubs. Mark these clearly to avoid damage during site preparation. List invasive species requiring removal and assess their extent.

Water drainage evaluation reveals wet areas, dry areas, and slopes that may erode. Walk the site during and after rain to observe water flow patterns. Low spots that pond become wetland planting areas. Dry, elevated areas need drought-tolerant species. Slopes over 5% require erosion control strategies.

Invasive species documentation creates a removal priority list. Photograph invasives and map their locations. Identify species precisely—Chinese Tallow, King Ranch Bluestem, Bermudagrass, Johnson Grass, and Ligustrum require different control methods. Estimate the percentage of area covered by each invasive.

Access and equipment considerations affect implementation methods. Can large equipment reach all areas? Consider equipment needs: tractor with seeder, ATV for access, mower for establishment maintenance. Assess your own capabilities honestly—some projects require contractor assistance while others suit do-it-yourself approaches.

Create a site assessment checklist documenting all observations. Photograph the entire site from multiple angles and specific problem areas. Date all documentation—you’ll treasure these “before” images later.

Step 2: Planning Your Restoration Project

Clear goals drive successful restoration. Define what you want to achieve: wildlife habitat for specific species, erosion control on slopes, water quality improvement, aesthetic beauty, agricultural tax exemption qualification, educational demonstration, or some combination. Specific goals shape species selection, design, and management approaches.

Habitat type selection depends on your ecoregion, site conditions, and goals. Options include tallgrass prairie, shortgrass prairie, savanna (scattered trees in grassland), woodland edge, wetland, or mixed habitat mosaics. Match habitat types to existing conditions—don’t try to create wetlands on hilltops or prairies in dense shade.

Scale and phasing decisions balance ambition with resources. Starting small with a demonstration area (quarter to half acre) allows you to learn techniques, observe results, and expand with confidence. Alternatively, tackling the entire project at once captures economies of scale. Consider phasing over 2 to 5 years, completing one section annually.

Timeline and budget require realistic assessment. Year one costs include site preparation, seeds or plants, and initial maintenance. Years two and three involve primarily labor for spot maintenance. Calculate costs for materials:

- Seed averages $100-$500 per acre

- Transplants cost $2,000-$15,000 per acre depending on density

- Equipment rental if needed

- Professional help for specialized tasks

Allow 2 to 3 years before judging success.

Species selection criteria narrow hundreds of possibilities to a manageable palette. Start with plants native to your specific ecoregion. Further filter by site conditions: sun/shade, soil type, moisture, and existing vegetation. Match plants to goals:

- Supporting monarch butterflies → include milkweeds

- Erosion control → emphasize deep-rooted grasses

- Aesthetics → select showy wildflowers with staggered bloom times

Design considerations transform plant lists into functional landscapes. In visible areas, create defined edges with mowed borders so the planting looks intentional, not neglected. Establish paths for maintenance access and viewing. Plan for diversity—aim for at least 15 to 40 species in prairie restoration to provide visual interest, wildlife value, and ecosystem resilience. Include:

- Grasses for structure

- Forbs for color and wildlife food

- Legumes for nitrogen fixation

Develop a project planning worksheet documenting goals, habitat types, timeline, budget, species list, and design notes. Connect with local Native Plant Society members for project reviews—experienced volunteers can spot potential problems before they occur.

Step 3: Site Preparation and Weed Control

Site preparation determines restoration success or failure more than any other factor. Inadequate weed control dooms projects to weed domination regardless of planting quality. Invest time here; shortcuts lead to frustration.

Invasive species removal strategies vary by species and infestation severity. Mechanical removal—mowing, tilling, or sod removal—works for annual weeds and light infestations but stimulates perennial weeds like Bermudagrass and Johnson Grass. Mowing alone rarely eliminates established invasives; it simply weakens them temporarily.

Herbicide application becomes necessary for persistent perennials and woody invasives. Use selective herbicides when possible to avoid damage to desirable plants. Glyphosate (Roundup and generics) is non-selective, killing all green vegetation, but breaks down quickly in soil. Apply when target plants are actively growing—late spring through early fall for most invasives. Multiple applications spaced several weeks apart are typically needed.

Timing considerations by species matter immensely:

- Chinese Tallow requires cut-stump treatment with concentrated herbicide immediately after cutting

- Bermudagrass responds best to herbicide in fall when translocating nutrients to rhizomes

- King Ranch Bluestem needs repeated applications as seed continues germinating

Creating a proper seedbed follows successful weed control. Light disking or scarification exposes mineral soil and creates seed-to-soil contact without destroying soil structure. Disturb the top 1 to 2 inches only. Avoid deep tilling which:

- Buries seeds too deeply

- Brings buried weed seeds to the surface

- Destroys beneficial soil organisms

- Disrupts natural soil layering

Ecoregion-specific considerations:

- Blackland Prairie’s heavy clay soils crust easily, preventing seedling emergence. Light scarification breaks the crust.

- Post Oak Savannah’s sandy soils drain rapidly and erode easily—minimize disturbance and consider mulching.

- Edwards Plateau’s rocky, thin limestone soils—spot planting between rocks may work better than broadcasting seed.

What NOT to do:

- Adding topsoil or compost (changes soil chemistry and favors weeds over natives)

- Over-tilling (destroys structure and stimulates weeds)

- Planting too soon after herbicide application (allow 2-4 weeks for breakdown)

- Leaving herbicide-killed vegetation standing thick (prevents seed-to-soil contact)

- Burning immediately before planting (removes litter that protects seeds)

Site preparation timelines extend from 3 months to a full year before planting. Herbicide treatment followed by fall seeding requires starting the previous spring—apply herbicide in May-June, retreat in August-September, and seed in November-January.

Step 4: Selecting Your Plant Palette

Diversity creates resilience, beauty, and wildlife value. Aim for at least 15 to 40 species in prairie restorations, with larger projects supporting even more diversity. Monocultures fail to provide season-long resources for wildlife and lack ecosystem stability.

Functional groups each play distinct ecological roles:

Warm-season grasses (growing May through September) form the structural backbone of most Texas ecosystems. These include Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, Indiangrass, and Switchgrass. Warm-season grasses typically constitute 60% to 70% of prairie seed mixes by weight.

Cool-season grasses (growing March through May, then again in fall) provide early spring green-up and some winter interest. Texas Cupgrass, Virginia Wildrye, and Texas Wintergrass fit this category. Include cool-season grasses at 5% to 10% of grass seed mix for diversity.

Forbs and wildflowers provide the color, much of the wildlife value, and most of the diversity. Include forbs at 30% to 40% of the overall seed mix. Select species with varied bloom times:

- Early (March-May): blue-eyed grass, purple coneflower, phlox

- Mid (June-July): black-eyed Susan, coreopsis, purple prairie clover

- Late season (August-October): asters, goldenrods, sunflowers

Legumes fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching soil naturally. Include at least 2 to 4 legume species: Illinois bundleflower, lead plant, partridge pea, and various wild indigos. Legumes often constitute 5% to 10% of the seed mix.

Woody plants (if appropriate to the habitat type) provide vertical structure, nesting sites, and food sources. Savanna and woodland edge restorations include native shrubs and trees at appropriate densities.

Ratio recommendations guide seed mix composition. For tallgrass prairie restoration, use roughly:

- 60% to 70% grasses (by seed weight, not seed count)

- 30% to 40% forbs

- Within forbs, include diverse families: asters, legumes, mints, and others

- No single species should exceed 20% of the total mix

Succession planning acknowledges that different species establish at different rates:

Early colonizers like annual sunflowers, black-eyed Susan, and partridge pea:

- Establish quickly (year one)

- Provide immediate color

- Help suppress weeds

- May decline in years 3 to 5 as slower species mature

Late-succession species like Big Bluestem, compass plant, and rattlesnake master:

- Take 2 to 4 years to establish

- Persist for decades once mature

- Provide long-term ecosystem stability

Wildlife considerations drive plant selection:

- Monarch butterflies require milkweeds; include at least 2 to 3 species native to your ecoregion

- Hummingbirds seek tubular red flowers like cardinal flower, coral honeysuckle, and standing cypress

- Ground-nesting birds need structural diversity and undisturbed areas during nesting season (April-August)

- Grassland birds prefer specific grass species and heights

Bloom time distribution ensures nectar availability spring through fall. Create a bloom calendar for your selected species to identify gaps and ensure continuous flowering.

Reference the ecoregion-specific sections for detailed plant lists tailored to your region. These lists narrow hundreds of Texas natives to the most appropriate species for your location.

Step 5: Planting Methods and Techniques

Seed versus transplants represents a fundamental choice affecting cost, labor, timeline, and visual impact.

Direct seeding advantages:

- Cost-effective: seeding one acre costs $100 to $500 versus $8,000 to $15,000 for transplants

- Natural plant densities and spacing

- Large areas become practical

- Creates authentic-looking ecosystems

Direct seeding disadvantages:

- Requires patience (slower establishment)

- Heavier weed competition initially

- Depends on proper timing

- Shows minimal first-year impact

Container plants advantages:

- Immediate visual impact

- Higher survival rates per individual plant

- Faster establishment

- Straightforward weed control around plants

- Works well for small areas (under half acre)

Container plants disadvantages:

- High cost for large-scale projects

- Labor-intensive installation

- Prohibitively expensive at high densities

Seeding techniques:

Hand broadcasting works beautifully for small areas under one acre:

- Mix seed thoroughly

- Divide into two equal portions

- Broadcast each portion in perpendicular passes for even coverage

- Include a carrier like sand or cracked corn to increase volume

- Rake lightly after broadcasting to improve seed-to-soil contact

- The key is getting seeds pressed into soil, not sitting on top

Drill seeding suits areas over one acre:

- Native grass drills create furrows, drop seed, and cover in one pass

- Rental drills may be available through Soil and Water Conservation Districts

- Follow drill calibration instructions carefully—native seeds vary enormously

- Achieves better seed-to-soil contact than hand broadcasting

Seed-to-soil contact importance cannot be overstated. Seeds sitting on top of thick dead vegetation or fluffy, loose soil often fail to germinate. Pack seeds gently into the soil surface using a cultipacker, roller, or simply walking over the seeded area. Livestock can be useful—cattle walked over a seeded area press seeds into soil effectively.

Dormant season seeding (November through January) is the primary recommendation for most Texas natives:

- Seeds lie dormant through winter

- Experience natural cold-moist stratification that breaks dormancy

- Germinate with spring warmth and rains

- This timing mimics natural seed dispersal

Specific timing varies by ecoregion:

- High Plains and Rolling Plains: Earlier seeding (November)

- Gulf Coast and South Texas Plains: As late as January

- Central and East Texas: December through January

Growing season seeding (May through June) works for warm-season species that germinate quickly without cold stratification, but success depends on reliable rainfall or irrigation.

Transplant installation requires attention to detail:

- Dig holes slightly wider and deeper than root balls

- Position plants at the same depth they grew in containers—too deep suffocates roots

- Remove containers carefully to avoid root damage

- Backfill with native soil (don’t add amendments)

- Firm gently to eliminate air pockets

- Water thoroughly

- Create a slight depression around each plant to catch water

Proper spacing for prairie restoration with transplants: space 1 to 3 feet apart in irregular patterns (not rows). Closer spacing creates quicker coverage but costs more. Wider spacing reduces costs but takes longer to fill in.

Initial watering after transplanting settles soil and provides moisture for root establishment:

- Water deeply immediately after planting

- Continue weekly deep watering (1 inch per week) for 6 to 8 weeks

- Deep, infrequent watering encourages deep rooting

Mulching considerations:

For gardens and small plantings: 2 to 3 inches of mulch around (not touching) transplants suppresses weeds and retains moisture. Use locally-sourced wood chips, shredded bark, or compost.

For large-scale prairie restoration: Generally avoid mulching. The scale makes it impractical and expensive. Mulch can introduce weed seeds. Native seedlings need bare soil to establish.

Exception: Erosion-prone slopes may benefit from light mulch (1 inch) to hold soil until plants establish. Use weed-free straw or native grass hay.

Step 6: Establishment Period (Year 1-2)

The establishment period tests patience. Year one typically looks underwhelming—sparse plants, lots of bare ground, plenty of weeds. Resist the urge to over-manage. Many natives invest energy in root systems before visible growth. Trust the process.

Watering requirements for seeded areas:

- Keep soil surface moist (not saturated) for first 4 to 6 weeks

- May require daily light watering during hot, dry weather

- Once seedlings reach 2 to 3 inches tall, transition to every 3 to 4 days

- By 8 to 12 weeks, reduce to weekly watering if rain doesn’t occur

- Wean plantings off supplemental water by late summer of year one

Watering requirements for transplants:

- Weekly deep watering (1 inch) for 6 to 8 weeks after installation

- Then every 10 to 14 days for remainder of first growing season

- Monitor soil moisture 4 to 6 inches deep

- By late fall of year one, most transplants survive without supplemental water

- Year two typically requires no irrigation unless drought is exceptional

First-year management focuses on helping natives establish while controlling weeds. Mowing becomes your primary tool. The guideline “mow the weeds, not the natives” means timing cuts to suppress fast-growing weeds without damaging slower-growing natives:

- Mow when weeds reach 8 to 12 inches tall

- Cut to 6 to 8 inches height

- This removes weed seed heads before maturity

- Frequency: monthly during spring and early summer, then less often

Weed management strategies:

Hand weeding around transplants removes competition effectively. Pull weeds when soil is moist so roots come out completely. Labor-intensive but effective for small areas.

Spot herbicide application controls invasive perennials without harming natives. Use a backpack sprayer or spray bottle to treat individual weeds. This requires plant identification skills—you must distinguish weed seedlings from native seedlings.

Selective mowing targets specific weed problems. Time mowing to cut seed heads before maturity. Mow high enough to avoid natives while still impacting target weeds.

Patience remains essential. Many natives look like “weeds” initially:

- Little Bluestem seedlings resemble wispy grass

- Compass plant grows only a basal rosette of leaves the first year

- Purple coneflower produces small leaf rosettes year one, blooming in year two

What to expect during establishment:

Year One: Mostly leaf growth, few flowers, lots of weeds. Seeded areas may look like 80% weeds, 20% natives. This is normal. Natives establish root systems below ground while weeds make flashy top growth.

Year Two: Stronger growth from natives, noticeably more flowers, better competition against weeds. The balance shifts to perhaps 60% natives, 40% weeds.

Year Three: Natives dominate, providing 80% or more coverage with minimal weed pressure.

The old saying “first year they sleep, second year they creep, third year they leap” holds true. Avoid judging success too early.

Step 7: Long-Term Management and Maintenance

After establishment, native plantings require minimal but important management to maintain diversity, vigor, and wildlife value.

Annual management practices vary by habitat type and goals:

Prescribed burning represents the gold standard for prairie and savanna management where practical:

- Fire removes accumulated dead material

- Stimulates new growth

- Suppresses woody encroachment

- Recycles nutrients

- Mimics natural disturbance regime

- Burn during dormant season (February-March) on a 2 to 4-year rotation

- Check local burn regulations and notify neighbors

- Many conservation districts offer burn training and assistance

- Never burn without proper training and firebreaks

Mowing regimes substitute for fire where burning is impractical:

- Mow in late winter (February) before spring growth begins, or late fall (November) after seed set

- Mowing height should be 6 to 8 inches minimum—lower cuts damage growing points

- Mowing every 2 to 3 years suffices for most prairies

- Annual mowing creates a more manicured appearance for suburban settings

- Remove clippings only if excessive—leaving them returns nutrients

Haying can be compatible with restoration if timed properly:

- Cut after July 15 to allow ground-nesting birds to complete nesting

- Hay after wildflowers have set seed

- One cutting per year typically works with prairie restoration

Spot treatment of invasive species continues as an ongoing task:

- Walk the restoration periodically

- Hand-pull invasive seedlings

- Spot-spray persistent perennials

- Early detection and rapid response prevent small problems from becoming large infestations

Monitoring and adaptive management track restoration progress:

Establish permanent photo points: Specific locations and directions photographed annually at the same time of year. Take spring, summer, and fall photos to capture seasonal variation.

Conduct species inventory updates every 2 to 3 years. Walk the site systematically and list all plant species present. Compare lists across years to track increasing native diversity and decreasing weed pressure.

Adjust management based on results:

- If a particular native species thrives, increase its proportion in future plantings

- If weeds persist in certain areas, increase management intensity

- If diversity seems low, add species that may have been missed initially

When to reseed or add species: After 2 to 3 years, if significant bare spots remain, reseed those areas. If diversity seems low compared to goals, add species that establish readily from transplants.

Signs of a healthy restoration:

- Increasing native plant diversity (new species appearing, initially planted species expanding)

- Decreasing weed pressure (less invasive species cover each year)

- Wildlife use (birds nesting, pollinators visiting, signs of small mammals)

- Structural diversity (mix of heights, densities, blooming times creating complex habitat)

By years 5 to 10, a mature restoration should largely maintain itself with minimal annual effort.

Long-term timeline:

- Years 3 to 5: Full maturity of most planted species

- Years 5 to 10: Natural recruitment of additional species from nearby remnants

- Years 10 to 20: Old-field characteristics with mature plant stands and complex soil ecology

- Years 20+: Surprising species additions and community developments

Established restorations improve with age, unlike most traditional landscaping that peaks early then declines.

Seasonal Planting Calendar for Texas

PRO TIP: Fall (September-November) is the best time to plant most Texas natives. Plants establish root systems during cool months and are ready to thrive when spring arrives.

Timing is critical for restoration success. Native plants evolved to germinate and establish during specific seasons. Working with these natural rhythms dramatically improves results.

Best Planting Times by Method

| Planting Method | Optimal Season | Why This Timing Works | Ecoregion Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dormant seed | November-January | Cold stratification, spring rains ready plants | Earlier (November) in High Plains; later (January) in Gulf Coast |

| Growing season seed | May-June | Warm-season germination without cold requirement | Works best with irrigation or in wetter ecoregions |

| Container natives | October-November, February-March | Cool temps reduce transplant stress, spring growth follows | Spring-only planting in Trans-Pecos; fall preferred in warmer regions |

| Bare root | December-February | Dormant plants transplant with minimal stress | Narrow window, mid-winter best |

Fall/winter dormant seeding (November through January) represents the primary recommendation for most Texas native plantings:

- Seeds lie dormant through winter

- Experience natural cold-moist stratification that breaks dormancy

- Germinate with spring warmth and rains

- This timing mimics natural seed dispersal

- Most native seeds require 30 to 60 days of cold, moist conditions to germinate properly

Fall transplanting (October through November) is the best choice for containerized natives:

- Cooling temperatures reduce transplant stress

- Plants develop root systems through fall and winter

- Drought-hardy by the following summer

- Spring growth comes naturally

- Watering requirements are minimal compared to spring/summer planting

Avoid summer planting (June through August) except in unusual circumstances:

- Extreme heat and limited rainfall create difficult establishment conditions

- Transplants require intensive irrigation

- Germination rates drop

- Stress increases mortality

Seasonal Maintenance Checklist

Spring (March-May):

- Monitor germination of dormant-seeded areas

- Hand-weed around new seedlings and transplants

- Begin mowing regimes if needed—watch for weeds outpacing natives

- Keep height at 6 to 8 inches minimum

- Enjoy early wildflowers—spring delivers most show in prairie plantings

- Good time to add missed species as transplants

Summer (June-August):

- Reduce or eliminate watering for established plantings (over 1 year old)

- Let plants experience natural drought—builds deep root systems

- Spot-treat invasive species while they’re actively growing

- Observe and photograph progress

- Collect seed from early-blooming species if building a seed bank

- Minimize disturbance during nesting season (April through August)

Fall (September-November):

- Optimal planting season for transplants—get them in by mid-November

- Collect seed for future propagation (take less than 10% from any population)

- Plan next year’s expansions

- Prepare new areas for winter seeding

- Apply herbicide to areas targeted for conversion

- Order seeds and plants for upcoming installations

- Enjoy late-season blooms from asters, goldenrods, and native sunflowers

Winter (December-February):

- Dormant season seeding time—broadcast seed on prepared areas

- Prescribed burning can occur during winter dormancy where appropriate

- Major invasive species management—cut and treat woody invasives

- Equipment maintenance prepares for upcoming season

- Review photo documentation and update management plans

- Planning time—attend native plant society meetings and workshops

Piney Woods Native Plants and Restoration

About the Piney Woods Ecoregion

The Piney Woods blanket far eastern Texas across 43 counties, extending from the Louisiana border west to a diffuse transition zone and from the Oklahoma border south to the Gulf Coast. This is Texas’s most humid region, receiving 40 to 58 inches of annual rainfall distributed fairly evenly throughout the year. The humid subtropical climate features hot summers, mild winters, and rare freezing events. Elevation ranges from near sea level to about 500 feet, creating gently rolling topography.

Soils are predominantly acidic sandy loams with high iron content, creating characteristic red and yellow subsoils. These acid soils (pH 4.5-6.0) contrast sharply with the neutral-to-alkaline soils dominating most of Texas. The acidic chemistry supports specialized plant communities including carnivorous pitcher plants and sundews in seepage bogs—species found nowhere else in the state.

Historically, pine-hardwood forests dominated the region with shortleaf pine, loblolly pine, longleaf pine (now rare), and various oaks, sweetgum, magnolia, and hickory. Currently, heavy development, pine plantation conversion, and fire suppression have altered most original forest structure.

Major cities include Texarkana, Tyler, Longview, Nacogdoches, and Lufkin. The region supports diverse wildlife including pine warblers, brown-headed nuthatches, and in remaining pristine habitats, red-cockaded woodpeckers and Louisiana black bears.

Native Grasses for Piney Woods

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Eastern Gamagrass | Tripsacum dactyloides | 4-8′ | Warm | High – seed, structure | Clump |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Splitbeard Bluestem | Andropogon ternarius | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Purpletop Tridens | Tridens flavus | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Virginia Wildrye | Elymus virginicus | 2-4′ | Cool | Medium – early seed | Bunch |

Native Forbs & Wildflowers for Piney Woods

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Bloom Time | Color | Sun/Shade | Wildlife Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Woodland Aster | Eurybia divaricata | 1-3′ | Aug-Oct | White | Shade | Pollinators |

| American Beautyberry | Callicarpa americana | 3-6′ | May-Jul | Purple | Part shade | Birds, bees |

| Carolina Jessamine | Gelsemium sempervirens | Vine | Feb-Apr | Yellow | Sun/shade | Bees |

| Turk’s Cap | Malvaviscus arboreus | 3-5′ | May-Nov | Red | Shade | Hummingbirds |

| Texas Lantana | Lantana urticoides | 3-6′ | Apr-Nov | Orange/yellow | Sun | Butterflies |

| Wild Blue Phlox | Phlox divaricata | 1-1.5′ | Mar-May | Blue | Part shade | Butterflies |

| Purple Coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | 2-4′ | May-Jul | Purple | Sun/part | Pollinators |

| Cardinal Flower | Lobelia cardinalis | 2-4′ | Jul-Oct | Red | Part shade | Hummingbirds |

Native Shrubs & Trees for Piney Woods

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Mature Size | Wildlife Value | Soil Preference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Magnolia | Magnolia grandiflora | 60-80′ | Birds, shelter | Moist, acidic |

| Flowering Dogwood | Cornus florida | 20-30′ | Birds, pollinators | Acidic, well-drained |

| Eastern Redbud | Cercis canadensis | 20-30′ | Bees, birds | Adaptable |

| Yaupon Holly | Ilex vomitoria | 15-25′ | Birds (berries) | Adaptable |

| American Holly | Ilex opaca | 40-50′ | Birds (berries) | Acidic, moist |

| Wax Myrtle | Morella cerifera | 10-15′ | Birds | Wet, acidic |

Restoration Considerations for Piney Woods

Chinese Tallow poses the most serious invasive threat. This aggressive tree from Asia produces thousands of seeds, spreads rapidly, and forms dense monocultures excluding natives. Control requires persistent effort—cut trees and immediately apply concentrated herbicide (triclopyr) to cut stumps. Expect resprouting; retreat resprouts repeatedly. Never allow trees to mature and set seed.

Soil management maintains the natural acidity natives require. Never add lime, which raises pH and favors weeds over acid-adapted natives. Embrace the region’s natural chemistry and work with it rather than against it.

Forest versus meadow balance creates wildlife diversity. While forests dominate naturally, maintaining some open areas benefits ground-nesting birds, butterflies, and sunlight-dependent wildflowers. Consider creating savanna (open woodland with scattered trees) or maintaining small prairie openings.

Estimated costs: $2,500-$4,000 for transplants or $800-$1,200 for mostly seed approach per acre.

Blackland Prairie Native Plants

About the Blackland Prairie Ecoregion

The Blackland Prairie stretches across north-central Texas in a crescent from the Red River near the Oklahoma border south past Austin. Named for its distinctive black, calcareous clay soils, this region once supported over 12 million acres of tallgrass prairie. Today, less than 1% of original prairie remains—nearly all converted to cropland due to rich soils and favorable growing conditions.

The region receives 30 to 40 inches of annual rainfall, with peak precipitation in spring (April-May) and secondary peaks in fall (September-October). Growing season extends 220 to 260 days. Summer drought typically occurs July through August.

Heavy, black clay soils (vertisols) characterize the region. These soils contain 40% to 60% clay with high shrink-swell capacity—they crack deeply during drought and expand when wet. While challenging to work, these soils are naturally fertile and support diverse prairie communities. Soil pH ranges from neutral to slightly alkaline (7.0-8.2).

Major cities include Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, and portions of Austin—home to over 7 million people. Urban and suburban restoration opportunities abound as homeowners and municipalities recognize native landscaping benefits.

Native Grasses for Blackland Prairie

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, structure | Bunch |

| Eastern Gamagrass | Tripsacum dactyloides | 4-8′ | Warm | High – seed | Clump |

| Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | 3-6′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Sideoats Grama | Bouteloua curtipendula | 1-2′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

Native Forbs & Wildflowers for Blackland Prairie

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Bloom Time | Color | Wildlife Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purple Coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | 2-4′ | May-Jul | Purple | Pollinators, seed |

| Black-eyed Susan | Rudbeckia hirta | 1-3′ | May-Sep | Yellow | Pollinators, seed |

| Lemon Beebalm | Monarda citriodora | 1-2′ | May-Jul | Pink/purple | Bees, butterflies |

| Maximilian Sunflower | Helianthus maximiliani | 3-10′ | Aug-Oct | Yellow | Pollinators, seed |

| Purple Prairie Clover | Dalea purpurea | 1-2′ | Jun-Aug | Purple | Bees, nitrogen fixer |

| Gayfeather | Liatris spp. | 2-4′ | Jul-Sep | Purple | Butterflies |

| Illinois Bundleflower | Desmanthus illinoensis | 2-4′ | May-Aug | White | Nitrogen fixer, seed |

Restoration Considerations for Blackland Prairie

Heavy clay soils create unique challenges. Vertisols crack deeply during drought and expand when wet. Avoid over-tilling, which destroys structure. Light disking or no-till seeding works better than deep cultivation. Clay crusting can prevent seedling emergence—time seeding to precede rain that softens crusts.

Urban restoration opportunities abound across the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. Even small pocket prairies contribute to regional conservation. Many restorations occur on small urban lots, parks, and suburban yards.

Invasive species include King Ranch Bluestem, Bermudagrass, and Johnson Grass. KRB particularly plagues the region—this South African grass spreads aggressively and outcompetes natives. Control requires repeated herbicide applications.

Sample plan for 0.25 acre suburban lot: Little Bluestem 8 lbs seed, Indiangrass 5 lbs, Sideoats Grama 3 lbs, plus 75 Purple Coneflower plants, 100 Black-eyed Susan plants, and accent trees. Estimated costs: $800-$1,500 for seed-based approach; $2,500-$4,000 for transplant-heavy design.

Edwards Plateau Native Plants (Texas Hill Country)

About the Edwards Plateau Ecoregion

The Edwards Plateau, better known as the Texas Hill Country, encompasses central Texas from San Antonio and Austin west to the Pecos River. This distinctive region features rugged limestone terrain, spring-fed rivers, and unique ecological communities. Elevation ranges from 1,000 to 3,000 feet with characteristic steep-sided valleys and flat-topped hills.

Rainfall varies significantly across the region from 33 inches in the east to 15 inches in the west, creating an east-west moisture gradient. Most precipitation falls in spring (April-May) and fall (September-October). Summer drought is typical. Growing season extends 240 to 270 days.

Shallow, rocky limestone soils characterize most of the region. Soil depth ranges from a few inches on hillsides to several feet in valleys. Highly calcareous soils (pH 7.5-8.5) contain abundant calcium carbonate. Despite shallow depth, these soils support remarkable plant diversity including endemic species found nowhere else.

Major cities include Austin, San Antonio, Kerrville, and Fredericksburg. The region supports endangered species including Golden-cheeked Warblers (nest exclusively in mature Ashe juniper) and Black-capped Vireos.

Native Grasses for Edwards Plateau

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Sideoats Grama | Bouteloua curtipendula | 1-2′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Texas Grama | Bouteloua rigidiseta | 1-2′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Curly Mesquite | Hilaria belangeri | 4-12″ | Warm | High – grazing, seed | Sod |

| Texas Cupgrass | Eriochloa sericea | 1-2′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Lindheimer Muhly | Muhlenbergia lindheimeri | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – ornamental | Bunch |

Native Forbs & Wildflowers for Edwards Plateau

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Bloom Time | Color | Sun/Shade | Wildlife Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bluebonnet (Texas) | Lupinus texensis | 1-2′ | Mar-May | Blue | Sun | Bees |

| Indian Blanket | Gaillardia pulchella | 1-2′ | Apr-Jul | Red/yellow | Sun | Pollinators |

| Greenthread | Thelesperma filifolium | 1-2′ | Mar-Jun | Yellow | Sun | Pollinators |

| Pink Evening Primrose | Oenothera speciosa | 6-18″ | Mar-Jun | Pink | Sun | Pollinators |

| Zexmenia | Wedelia texana | 1-2′ | Apr-Nov | Yellow | Sun/part | Butterflies |

| Fall Aster | Symphyotrichum oblongifolium | 1-3′ | Sep-Nov | Purple | Sun | Pollinators |

| Rock Rose | Pavonia lasiopetala | 2-4′ | Apr-Oct | Pink | Part shade | Hummingbirds |

| Scarlet Sage | Salvia coccinea | 1-3′ | Apr-Oct | Red | Part shade | Hummingbirds |

| Flame Acanthus | Anisacanthus quadrifidus | 3-4′ | May-Oct | Orange/red | Sun/part | Hummingbirds |

Native Shrubs & Trees for Edwards Plateau

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Mature Size | Wildlife Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plateau Live Oak | Quercus fusiformis | 30-40′ | Acorns, shelter | Evergreen |

| Texas Red Oak | Quercus buckleyi | 30-50′ | Acorns, wildlife | Fall color |

| Ashe Juniper | Juniperus ashei | 15-30′ | Birds, shelter | Golden-cheeked Warbler habitat |

| Texas Persimmon | Diospyros texana | 20-30′ | Wildlife fruit | Drought-hardy, beautiful bark |

| Agarita | Mahonia trifoliolata | 3-6′ | Birds (berries), bees | Evergreen, early blooms |

| Texas Mountain Laurel | Sophora secundiflora | 10-15′ | Bees | Fragrant purple blooms |

| Mexican Buckeye | Ungnadia speciosa | 15-30′ | Bees | Early spring blooms |

| Cedar Elm | Ulmus crassifolia | 50-70′ | Birds, shade | Fall blooms |

Restoration Considerations for Edwards Plateau

Rocky limestone soils require adapted approaches. Drilling through rock is impractical—broadcast seeding or spot planting between rocks works better. Thin soils limit water-holding capacity, making drought tolerance critical. Select species naturally occurring on limestone.

Golden-cheeked Warbler habitat complicates juniper management. These endangered songbirds nest exclusively in mature Ashe juniper with shredding bark. Complete juniper removal harms warblers. Selective thinning maintains some mature junipers while opening areas for grassland restoration. Consult with U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service if warblers may be present (generally Austin area westward).

Spring-fed streams create oasis habitats requiring protection. Maintain riparian buffer zones with intact native vegetation. These corridors support diverse wildlife and protect water quality.

Ashe Juniper management sparks debate. While juniper encroachment has degraded grasslands, complete removal eliminates habitat value for numerous species. Aim for savanna structure—scattered mature trees with grassland matrix—rather than elimination or dense woodland.

Sample plan for 2 acres rural: Little Bluestem 25 lbs seed, Sideoats Grama 15 lbs, Texas Grama 10 lbs, plus Bluebonnet 5 lbs seed, Fall Aster 100 plants, retain selective mature Ashe Junipers. Estimated costs: $1,200-$2,000 for seed-based restoration.

Gulf Coast Prairies & Marshes Native Plants

About the Gulf Coast Prairies & Marshes Ecoregion

The Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes extend along the Texas coastline from the Louisiana border to the Mexican border, encompassing a 30 to 80-mile-wide band inland. This low-lying region includes major cities like Houston, Galveston, Corpus Christi, and Beaumont. Elevation ranges from sea level to about 150 feet, with flat to gently rolling terrain.

Annual rainfall varies from 30 inches in the south to 50 inches in the east, making this one of Texas’s wettest regions. The humid subtropical climate features hot, humid summers and mild winters with rare freezes. Growing season extends 280 to 320 days—the longest in Texas. Salt spray, hurricanes, and occasional tropical storms shape plant communities.

Less than 1% of original coastal prairie remains—mostly converted to rice farming, urban development, and industrial uses. Unique features include critical habitat for migrating birds along the Central Flyway, remnant populations of the critically endangered Attwater’s Prairie Chicken, and extensive salt marsh systems. The region supports over 400 bird species annually, making it internationally significant for bird conservation.

Native Grasses for Gulf Coast

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | 3-6′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Eastern Gamagrass | Tripsacum dactyloides | 4-8′ | Warm | High – seed | Clump |

| Gulf Coast Muhly | Muhlenbergia capillaris | 2-3′ | Warm | Medium – ornamental | Bunch |

| Seacoast Bluestem | Schizachyrium littorale | 2-3′ | Warm | High – coastal stabilization | Bunch |

| Saltgrass | Distichlis spicata | 6-18″ | Warm | High – salt tolerance | Rhizomatous |

Native Forbs & Wildflowers for Gulf Coast

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Bloom Time | Color | Wildlife Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texas Bluebonnet | Lupinus texensis | 1-2′ | Mar-May | Blue | Bees |

| Indian Paintbrush | Castilleja indivisa | 1-2′ | Mar-May | Red/orange | Hummingbirds |

| Black-eyed Susan | Rudbeckia hirta | 1-3′ | May-Sep | Yellow | Pollinators, seed |

| Purple Coneflower | Echinacea purpurea | 2-4′ | May-Jul | Purple | Pollinators |

| Lanceleaf Coreopsis | Coreopsis lanceolata | 1-2′ | Apr-Jun | Yellow | Pollinators |

| Frogfruit | Phyla nodiflora | 3-6″ | Apr-Oct | White/pink | Butterflies (groundcover) |

| Seaside Goldenrod | Solidago sempervirens | 2-5′ | Sep-Nov | Yellow | Pollinators |

| Scarlet Sage | Salvia coccinea | 1-3′ | Apr-Oct | Red | Hummingbirds |

| Texas Aster | Symphyotrichum drummondii | 2-4′ | Sep-Nov | Purple/blue | Pollinators |

Restoration Considerations for Gulf Coast

Salt tolerance becomes critical near the coast. Within 5 miles of saltwater, select species tolerating salt spray and occasional saltwater inundation during storm surge. Seacoast Bluestem, Saltgrass, Gulf Coast Muhly, and Seaside Goldenrod thrive in these conditions.

Hurricane-resistant species matter in this storm-prone region. Live Oak’s low, spreading form and strong wood withstand high winds better than upright trees. Native plants generally outperform exotic ornamentals during storms due to deeper root systems and flexible growth habits.

Chinese Tallow and Bermudagrass represent the most serious invasive threats. Tallow forms dense monocultures in wetland edges and disturbed areas. Both require aggressive, persistent control efforts. The humid climate accelerates invasive growth, making vigilance essential.

Whooping Crane habitat importance makes coastal restoration especially valuable. The critically endangered Whooping Crane winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and surrounding areas. Coastal prairie and marsh restoration supports cranes and numerous other migratory species.

Sample plan for 1 acre: Big Bluestem 15 lbs seed, Indiangrass 10 lbs, Little Bluestem 10 lbs, Switchgrass 5 lbs, plus forbs and woody accents. Estimated costs: $1,000-$2,000 for seed-based approach; $3,500-$5,500 with transplants.

Post Oak Savannah Native Plants

About the Post Oak Savannah Ecoregion

The Post Oak Savannah forms a transitional band between eastern forests and central prairies, extending from the Red River south through the Brazos Valley to the Gulf Coast. This region includes College Station, Huntsville, and portions of Austin. Elevation ranges from 200 to 600 feet with gently rolling terrain.

Annual rainfall varies from 30 to 45 inches, decreasing from east to west. Growing season extends 240 to 280 days. Soils are predominantly sandy loams with moderate acidity (pH 5.5-6.5). Historically, the region featured post oak savanna—scattered post oak trees over a grassland matrix with denser woodland along streams. Fire maintained the open structure.

The region serves as important breeding habitat for grassland birds where prairie openings persist, and supports transitional flora mixing eastern and western species.

Native Grasses for Post Oak Savannah

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Big Bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Eastern Gamagrass | Tripsacum dactyloides | 4-8′ | Warm | High – seed | Clump |

| Splitbeard Bluestem | Andropogon ternarius | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

Key Native Plants for Post Oak Savannah

Forbs: Purple Coneflower, Black-eyed Susan, Butterflyweed, Texas Lantana, Frostweed, Wild Blue Phlox, Standing Cypress, Turk’s Cap

Woody Species: Post Oak, Blackjack Oak, Eastern Redbud, Yaupon Holly, American Beautyberry, Mexican Plum, Roughleaf Dogwood, Flameleaf Sumac

Restoration Considerations

Sandy soils require specific management. These well-drained soils dry quickly during drought but erode easily when disturbed. Minimize soil disturbance during site preparation. Established natives stabilize sand with deep root systems.

Transitional species selection offers flexibility. The Post Oak Savannah supports plants from both eastern forests (post oak, yaupon) and western prairies (little bluestem, Indiangrass). This diversity creates opportunities for mixed habitat restoration featuring woodland, savanna, and prairie elements.

Fire’s role in maintaining savanna structure was historically critical. For large-scale restoration, consider prescribed burning on 3-5 year rotations. For small properties, selective tree thinning and mowing can substitute.

Estimated costs: $1,500-$2,500 for primarily seed-based restoration (2 acres).

Cross Timbers Native Plants

About the Cross Timbers Ecoregion

The Cross Timbers extends across north-central Texas in alternating bands of forest and prairie running north-south. This region includes portions of Fort Worth, Denton, Weatherford, and Mineral Wells. The distinctive pattern—visible from space—consists of sandy ridges supporting oak woodlands alternating with clay valleys containing prairies.

Annual rainfall ranges from 25 to 35 inches with most precipitation in spring and fall. Growing season extends 220 to 240 days. Soils alternate between sandy loams on ridges (supporting post oak and blackjack oak forests) and clay loams in valleys (supporting prairie). This soil pattern creates the characteristic timber-prairie mosaic.

Fire played a critical role in maintaining structure—woodlands occupied fire-protected ridges while fire-swept valleys remained prairie. Without fire, woodlands have expanded into former prairie openings.

Native Grasses for Cross Timbers

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Bluestem | Schizachyrium scoparium | 2-4′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Indiangrass | Sorghastrum nutans | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Big Bluestem | Andropogon gerardii | 4-7′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Sideoats Grama | Bouteloua curtipendula | 1-2′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Switchgrass | Panicum virgatum | 3-6′ | Warm | High – seed, cover | Bunch |

| Silver Bluestem | Bothriochloa saccharoides | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

Key Native Plants for Cross Timbers

Forbs: Purple Coneflower, Black-eyed Susan, Lemon Beebalm, Maximilian Sunflower, Illinois Bundleflower, Purple Prairie Clover, Engelmann’s Daisy, Texas Lantana, Gayfeather, Scarlet Sage

Woody Species: Post Oak, Blackjack Oak, Texas Red Oak, Eastern Redbud, Roughleaf Dogwood, Flameleaf Sumac, Mexican Plum, Rusty Blackhaw

Restoration Considerations

Woodland versus prairie balance requires strategic planning. Decide whether to create open prairie, oak savanna, or woodland based on existing conditions and goals. Dense woodlands benefit from thinning to create savanna structure.

Prescribed fire maintains the historic mosaic pattern. Burning prairie openings every 3-5 years maintains structure while protecting wooded areas with firebreaks.

Woody encroachment from red cedar and mesquite alters habitat. Eastern Red Cedar invades from the east while mesquite spreads from the west. Control young trees through cutting or herbicide; mature trees provide wildlife value and can be retained selectively.

Sandy versus clay soils within the same property require different plant palettes. Sandy ridges suit post oak, blackjack oak, and little bluestem. Clay valleys favor big bluestem, Indiangrass, and forbs tolerating heavier soils.

Estimated costs: $2,000-$3,500 for primarily seed-based approach (3 acres).

South Texas Plains Native Plants

About the South Texas Plains Ecoregion

The South Texas Plains, also known as the Tamaulipan thornscrub or South Texas brush country, extends from San Antonio south to the Rio Grande Valley and from the Gulf Coast west to the Edwards Plateau. This vast region includes San Antonio, Laredo, McAllen, and Brownsville.

Annual rainfall varies from 20 to 30 inches, with a bimodal pattern peaking in spring (May-June) and fall (September-October). Winter is mild with rare freezes in northern portions and almost frost-free conditions in the Rio Grande Valley. Growing season extends 300 to 340 days—among the longest in the United States.

Historically, the region featured dense thornscrub—a mixture of thorny shrubs, small trees, and subtropical species forming nearly impenetrable thickets interspersed with grassland openings. Unique features include subtropical species at their northern range limit, critical wildlife corridors for endangered ocelots and jaguarundis, and exceptional birding diversity (over 500 species recorded).

Native Grasses for South Texas Plains

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Height | Season | Wildlife Value | Growth Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffalograss | Bouteloua dactyloides | 4-8″ | Warm | High – grazing, seed | Sod |

| Curly Mesquite | Hilaria belangeri | 4-12″ | Warm | High – grazing, seed | Sod |

| Sideoats Grama | Bouteloua curtipendula | 1-2′ | Warm | High – seed | Bunch |

| Pink Pappusgrass | Pappophorum bicolor | 1-2′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Cane Bluestem | Bothriochloa barbinodis | 2-4′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

| Texas Grama | Bouteloua rigidiseta | 1-2′ | Warm | Medium – seed | Bunch |

Key Native Plants for South Texas Plains

Forbs: Texas Bluebonnet, Indian Blanket, Purple Horsemint, Zexmenia, Texas Lantana, Turk’s Cap, Frogfruit, Mealy Blue Sage, Blackfoot Daisy, Tropical Sage

Woody Species: Honey Mesquite, Texas Persimmon, Texas Ebony, Guajillo, Blackbrush Acacia, Granjeno, Anacacho Orchid Tree, Brasil, Texas Mountain Laurel, Retama

Restoration Considerations

Thornscrub ecosystem restoration differs fundamentally from prairie restoration. Rather than open grassland, aim for mosaic of dense brush thickets and grassland openings. Thickets provide critical cover for wildlife, especially endangered cats like ocelots and jaguarundis.

Wildlife corridor importance makes every restoration valuable. South Texas has lost over 95% of original brush, fragmenting habitat. Restoration reconnects fragments, allowing wildlife movement between protected areas. Even small properties contribute to landscape connectivity.

Drought tolerance is essential. Select species surviving on rainfall alone—supplemental irrigation shouldn’t be necessary after establishment. Many subtropical species are exceptionally drought-hardy once established.

Subtropical species at northern range limits require careful siting. Some plants (Texas Ebony, Retama) are frost-sensitive and should be planted in warmer microclimates in northern portions of the region.

Buffelgrass invasion threatens native brush country. This African grass, intentionally planted for forage, now invades wildlands, creating fire fuel that burns native brush. Control requires vigilance.

Sample plan for 5 acres: Grassland openings (3 acres) with Buffalograss 15 lbs seed, Sideoats Grama 15 lbs, Curly Mesquite 10 lbs. Brush restoration (2 acres) with 25 Honey Mesquite trees, 20 Texas Persimmon, 50 Guajillo shrubs, and more. Estimated costs: $2,500-$4,500 for seed and transplants.

Llano Uplift Native Plants

About the Llano Uplift Ecoregion

The Llano Uplift appears as a distinct granite dome in the heart of Central Texas, centered around the town of Llano and including Enchanted Rock State Natural Area. This small ecoregion (about 1,500 square miles) creates an island of unique geology within the surrounding Edwards Plateau. Elevation ranges from 800 to 1,800 feet.

Distinctive pink granite bedrock underlies the region, creating dramatic dome formations, thin sandy soils derived from weathered granite, and unique vegetation communities. The granite outcrops support endemic plant species found nowhere else in the world.

Key grasses: Little Bluestem, Sideoats Grama, Curly Mesquite, Texas Grama, Lindheimer Muhly, Seep Muhly

Key forbs: Bluebonnet, Firewheel, Twist-leaf Yucca, Lemon Paintbrush, Rock Quillwort (endemic), Texas Star, Violet Wood Sorrel, Bladderpod, Tahoka Daisy

Key woody species: Texas Red Oak, Shin Oak, Texas Persimmon, Agarita, Texas Mountain Laurel, Cedar Elm, Live Oak

Restoration Considerations

Granite outcrops and thin soils require specialized approaches. Traditional seeding doesn’t work on exposed granite—focus restoration on soil pockets, crevices, and areas with at least several inches of soil. Rock garden techniques apply: locate soil pockets, clear invasive plants, and install appropriate container-grown plants.

Endemic species warrant special protection. Plants like Rock Quillwort and specific Bladderpod species are found only in the Llano Uplift. Avoid disturbing populations.

Seasonal pools (vernal pools) on granite surfaces support unique plants and fairy shrimp. These shallow depressions fill with winter rains and dry by summer. Protect hydrology—don’t drain or fill pools.

Estimated costs: $2,000-$3,500 (transplant-heavy due to difficult seeding conditions on rock).

Rolling Plains Native Plants

About the Rolling Plains Ecoregion

The Rolling Plains extend across west-central Texas from the Cross Timbers west to the High Plains escarpment. The region includes Abilene, Wichita Falls, Vernon, and San Angelo. Elevation ranges from 1,000 to 2,500 feet with characteristic rolling, dissected topography.

Annual rainfall ranges from 20 to 30 inches, decreasing from east to west. Summer drought is typical and severe. Growing season extends 210 to 230 days. The region experiences hot summers, cold winters with occasional severe freezes, and frequent high winds.

Key grasses: Little Bluestem, Sideoats Grama, Blue Grama, Buffalograss, Western Wheatgrass, Sand Bluestem

Key forbs: Purple Prairie Clover, White Prairie Clover, Illinois Bundleflower, Dotted Gayfeather, Maximilian Sunflower, Purple Coneflower, Blacksamson Echinacea, Plains Zinnia, Scarlet Globemallow

Key woody species: Honey Mesquite, Skunkbush Sumac, Sand Sage, Four-wing Saltbush, Netleaf Hackberry, Chittamwood

Restoration Considerations

Wind exposure requires attention. Strong prevailing winds dry soils, break plant stems, and make establishment challenging. Shorter-statured plants generally fare better than tall species.

Mesquite management balances control with wildlife value. Dense mesquite thickets reduce grass production but provide crucial wildlife cover and food (pods). Rather than complete removal, consider thinning to savanna structure—scattered mesquites with grassland understory.

Sand versus clay soil within the region creates different plant communities. Match species to specific soils.

Estimated costs: $3,500-$6,000 for seed-based restoration (10 acres).

High Plains Native Plants

About the High Plains Ecoregion

The High Plains occupy the Texas Panhandle including Amarillo, Lubbock, Plainview, and surrounding counties. This region forms the southern end of the Great Plains, characterized by flat topography, shortgrass prairie, and agricultural dominance. Elevation ranges from 3,000 to 4,500 feet—the highest in Texas.

Annual rainfall is low at 15 to 22 inches. Growing season is relatively short at 180 to 210 days due to late spring frosts and early fall freezes. Wind is constant and often severe, with dust storms possible.

Key grasses: Blue Grama, Buffalograss, Sideoats Grama, Western Wheatgrass, Little Bluestem, Sand Dropseed

Key forbs: Purple Prairie Clover, White Prairie Clover, Scarlet Globemallow, Plains Zinnia, Dotted Gayfeather, Plains Blackfoot, Wooly Paperflower, Tahoka Daisy, Blacksamson Echinacea, Maximilian Sunflower

Key woody species: Four-wing Saltbush, Sand Sage, Skunkbush Sumac, Yucca, Cholla Cactus

Restoration Considerations

Extreme wind exposure affects all plantings. Select short-statured, wind-tolerant species. Tall plants often break or lodge.

Limited growing season requires timing attention. Use dormant season seeding (November-January) to ensure cold stratification and early spring germination.

Shortgrass prairie ecosystem differs fundamentally from tallgrass prairie. Expect short vegetation (6-18 inches typical) rather than shoulder-high plants. This is natural—not a sign of failure.

Playa wetlands warrant special protection. These seasonal wetlands are critical for migratory birds and endemic invertebrates.

Estimated costs: $4,000-$7,000 for seed-based restoration (20 acres CRP).

Trans-Pecos Native Plants (Chihuahuan Desert)

About the Trans-Pecos Ecoregion

The Trans-Pecos encompasses far west Texas including El Paso, Big Bend National Park, the Davis Mountains, and surrounding desert basins and mountain ranges. This is Texas’s most arid and geologically diverse region. Elevation varies dramatically from 2,500 feet in desert basins to over 8,000 feet in mountain peaks.

Annual rainfall ranges from just 8 inches in desert lowlands to 16 inches in higher mountains. Precipitation falls primarily in late summer monsoon season (July-September). Temperature extremes are severe—summer highs exceeding 110°F and winter lows occasionally below 0°F at high elevations.

Key grasses: Black Grama, Sideoats Grama, Blue Grama, Tobosa, Curly Mesquite, Cane Bluestem

Key forbs: Desert Marigold, Paperflower, Blackfoot Daisy, Desert Zinnia, Plains Zinnia, Trailing Four O’Clock, Scarlet Globemallow, Desert Willow, Autumn Sage, Damianita

Key woody species: Ocotillo, Lechuguilla, Sotol, Cenizo (Texas Sage), Creosote Bush, Honey Mesquite, Catclaw Acacia, Mormon Tea, Allthorn, Desert Willow

Restoration Considerations

Extreme drought tolerance is non-negotiable. No irrigation should be necessary after establishment (6-12 months). Select only species naturally occurring in desert conditions.

Desert ecosystem restoration differs from grassland restoration. Rather than continuous grass cover, expect open spacing with bare ground between plants—this is natural desert structure. Aim for 30-60% cover, not 100%.

Elevation zones within the region create distinct plant communities. Basin floors (2,500-3,500 feet) feature creosote, lechuguilla, and other low-desert species. Mid-elevations (3,500-5,500 feet) support desert grasslands. Mountains (5,500+ feet) have oak-juniper woodlands.

Summer monsoon season is optimal planting time. Unlike most of Texas, Trans-Pecos receives significant summer rain. Late summer (July-August) plantings take advantage of monsoon moisture.

Estimated costs: $3,000-$5,000 (primarily transplants due to difficulty establishing from seed in desert conditions, 2 acres).

Where to Source Native Plants in Texas

Understanding Seed Sourcing and Genetic Appropriateness

Local ecotype selection matters for restoration success. Plants from local populations carry genetic adaptations to local conditions—drought timing, temperature extremes, soil chemistry, and pest pressures. Seed collected 50 miles away performs better than genetically identical seed from 500 miles away.

General rule: Source seed from within 200 to 300 miles of your planting site and from similar ecoregions. Cross-ecoregion sourcing risks introducing poorly adapted genetics.

Red flags:

- “Native” plants sourced from outside Texas

- Cultivar names indicating heavy breeding

- Suspiciously low prices suggesting non-local seed sources

- Suppliers unwilling to disclose seed origin

Native Seed Suppliers (By Region)

Statewide Suppliers:

- Native American Seed (Junction) – Hill Country, statewide shipping. Excellent Hill Country species selection, wildflower mixes, custom blends.

- Bamert Seed Company (Muleshoe) – Panhandle, Great Plains species. Strong grass selection, large-scale restoration quantities.

- Turner Seed Company (Breckenridge) – Rolling Plains, Cross Timbers. Conservation seed specialist, custom mixes.

- Douglass King Seed (San Antonio) – South Texas, Central Texas. South Texas brush country specialists.

- Nature’s Finest Seed (Dallas/Waco) – North Texas, Blackland Prairie.

What to ask suppliers:

- Where was this seed collected? (specific county/region)

- What is the Pure Live Seed percentage?

- Is this straight species or cultivar?

- When was seed collected? (fresh seed germinates better)

- What’s the recommended seeding rate for my application?

Budget: Expect $100-$500 per acre for diverse seed mixes. Individual species seed costs $50-$400 per pound depending on species, availability, and quantity.

Native Plant Nurseries (By Region)

East Texas: Almost Eden (Murchison), Madrone Nursery (Sheridan)

North Texas (DFW): Archie’s Gardenland, North Haven Gardens (Dallas), Rohde’s Nursery (Fort Worth), Gecko Ranch (Mansfield)

Central Texas (Austin-San Antonio): The Natural Gardener (Austin), Barton Springs Nursery (Austin), It’s About Thyme (Austin), Rainbow Gardens (San Antonio), Native Son Nursery (New Braunfels)

South Texas: Native Backyards (Laredo), Native Plant Project Lower Rio Grande Valley Nursery (Edinburg/Weslaco)

Gulf Coast: Maas Nursery (Seabrook), Buchanan’s Native Plants (Houston)

Buying tips:

- Spring (March-May) and fall (September-November) offer best selection

- Call ahead for availability of specific species

- Many offer bulk pricing for large projects

- Join Native Plant Society chapters for plant sale access (members get first dibs, better prices)

Cost Estimates and Budget Planning

Seeds:

- Native seed mixes (prairie/meadow): $100-$500 per acre

- Individual grass species: $50-$200 per pound

- Forb seed: $100-$400 per pound

Container Plants:

- 4-inch container natives: $4-$8 each

- 1-gallon container: $12-$25 each

- 5-gallon natives: $25-$60 each

- Native trees (5-15 gallon): $40-$150 each

Per-Acre Restoration Costs:

- Seed-only prairie: $500-$1,500 total

- Seed plus focal area transplants: $2,000-$5,000 total

- Mostly transplants (high density): $8,000-$15,000 total

- Maintenance years 1-3: $200-$500 annually

- Maintenance year 4+: Under $200 annually

Common Challenges and Solutions

WARNING: Never collect native plants from the wild without landowner permission. Many Texas natives are protected by law. Always source from reputable native plant nurseries.

Dealing with Invasive Species

Top Invasive Plants by Ecoregion:

All Regions: King Ranch Bluestem (South African grass), Bermudagrass (extremely competitive sod-former), Johnson Grass (spreads via seed and rhizomes)

East Texas (Piney Woods): Chinese Tallow (most serious—forms monocultures), Japanese Climbing Fern, Cogongrass, Chinaberry

Central/South Texas: Ligustrum, Nandina, Chinese Privet, Giant Reed (Arundo donax)

Species-Specific Guidance:

Chinese Tallow: Cut trees and immediately paint stumps with concentrated triclopyr or glyphosate. Expect resprouting—retreat multiple times. Aggressive treatment over 3-5 years can achieve control.

Bermudagrass: Multiple herbicide applications (glyphosate) spaced 4-6 weeks apart. Fall applications most effective when grass translocates nutrients to rhizomes. Takes 1-2 years of persistent effort.