Red-cockaded Woodpecker: Texas Conservation Success

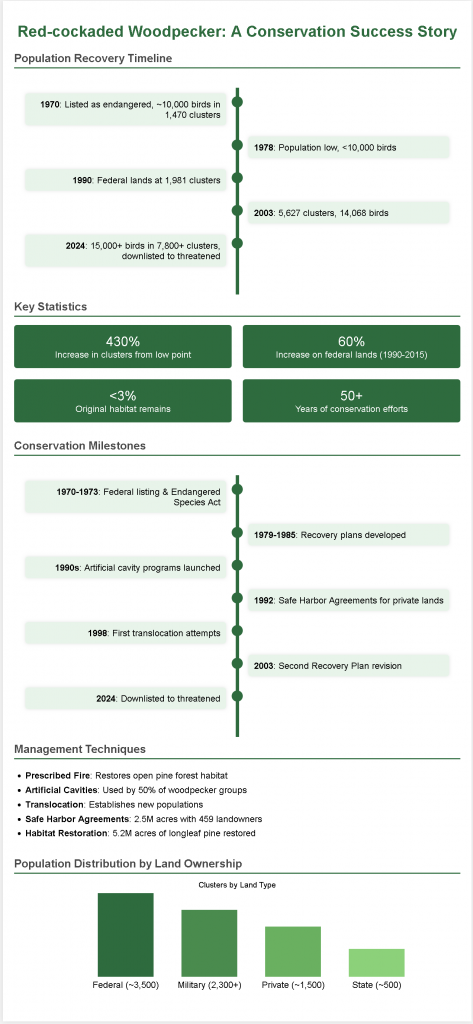

After 54 years on the endangered species list, the Red-cockaded Woodpecker (RCW) in Texas stands as a living emblem of hope for modern conservation. In the dense, ancient forests of the East Texas Pineywoods, recovery efforts have reversed decades of decline for this small black-and-white bird, symbolizing one of America’s greatest comeback stories. In 2024, the RCW was officially “down listed” from endangered to threatened—a remarkable turnaround driven by the perseverance of Texas conservationists, scientists, and local communities.

Moreover, nowhere is this transformation more apparent than in Sam Houston National Forest, where more than 350 breeding pairs thrive—the first population west of the Mississippi River to achieve recovery goals set by federal and state agencies. Beyond the bird’s survival, its comeback signals something bigger: the return of the Pineywoods as an ecological stronghold, sheltering hundreds of animal and plant species and rejuvenating an ecosystem that once spanned 90 million acres across the American South.

This is the story of a bird, a forest, and a state that refused to surrender to extinction. This is Texas’s Pineywoods, reborn.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker Recovery

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker is unique among North America’s woodpeckers, being the only species that excavates nesting cavities exclusively in living pine trees—a process taking years of diligent work. These birds live in social family groups, with adult “helper” birds assisting breeding pairs in raising young, a strategy that enhances colony survival.

RCWs engineer their own defensive fortresses: drilling resin wells around cavity entrances to create sticky sap barriers that deter snakes and other predators. These adaptations benefit not only their own broods but over 27 other animal species, including rare bats, flying squirrels, and even reptiles that repurpose abandoned cavities.

Due to habitat loss and fire suppression, RCW numbers in Texas hit a low of 925 birds in 1994. Today,

Fortunately, thanks to prescribed burns, careful habitat management, and intensive monitoring, that number has swelled to over 1,500 individuals. The best places to see RCWs are W.G. Jones State Forest near Conroe and select stands within Sam Houston National Forest, where early morning excursions offer the best odds of spotting these elusive ecosystem engineers.

Geographic Overview & Foundation

The East Texas Pineywoods encompass a vast, humid region covering 23,500 square miles—making up much of Texas’s green eastern border. With a subtropical, high-rainfall climate (35–60 inches annually), this ecoregion represents the western extension of southern U.S. pine forests, historically famed for their towering longleaf, slash, shortleaf, and loblolly pines.

A centerpiece of the Pineywoods, the Big Thicket National Preserve, is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve recognized for its bewildering ecological diversity. The land features rolling hills, pine uplands, and hardwood bottomlands, fostering habitats for rare orchids, carnivorous plants, and a stunning variety of wildlife—all anchored by the mighty longleaf pine.

Longleaf Pine Ecosystem Crisis & Recovery

A century ago, 90 million acres of longleaf pine forest blanketed the American South. Today, a staggering 97% of that native habitat is gone, with Texas harboring less than 60,000 scattered acres. The remaining longleaf pine stands represent critical endangered species habitat for the Red-cockaded Woodpecker and other wildlife. owe their survival to fire—a natural process now mimicked through prescribed burns managed by dedicated teams.

Corporate giants like Google and Manulife have funded restoration projects, facilitating the reestablishment of longleaf ecosystems critical for RCWs, rare pitcher plants, sundews, and native orchids. Fire’s role is indispensable: without regular burns, hardwoods invade, shading out the open pine glades on which RCWs depend.

Additionally, This landscape supports some of the world’s most specialized flora and fauna, thriving in bogs and open pine savannas found nowhere else in Texas.

Big Thicket: Biological Crossroads

Dubbed the “biological crossroads of North America,” Big Thicket National Preserve is where eastern hardwoods, Gulf coast plains, and central prairies converge, creating a mosaic unlike any other U.S. national park. Home to over 1,000 plant species and 289 recorded birds, its bogs and bottomlands shelter everything from desert cacti to swamp cypress.

Big Thicket’s 97,000 acres span nine management units linked by six waterways, boasting over 40 miles of hiking trails and multiple paddling routes—making it a must-visit for ecotourists, hikers, and naturalists seeking diversity on every trail.

Wildlife Beyond the Red-cockaded Woodpecker

While the RCW is the Pineywoods’ avian superstar, these forests teem with life. The Louisiana Black Bear, once extirpated from East Texas, is making a quiet return to bottomland corridors. Pine specialists—such as the Pine Warbler, Brown-headed Nuthatch, and Bachman’s Sparrow—depend on mature pine stands for nesting and foraging.

Furthermore, Aquatic habitats support River Otters and an array of amphibians, while carnivorous plants––including pitcher plants, sundews, and bladderworts––flourish in the forest’s scattered bogs. Winter brings roosting Bald Eagles and a host of hawk species, rounding out one of Texas’s richest hunting grounds for wildlife enthusiasts.

Red-cockaded Woodpecker Conservation Success Stories

Sam Houston National Forest was the first site west of the Mississippi to meet all RCW recovery benchmarks—a landmark for both state and national conservation efforts. These milestones were achieved ahead of federal timelines thanks to:

- Aggressive prescribed burn programs restoring natural fire cycles.

- Private landowner incentives and conservation easements.

- Research collaborations between Texas A&M, U.S. Forest Service, and universities.

- Volunteer monitoring and active citizen science networks, including eBird and iNaturalist.

These collective actions not only rebounded the RCW but also catalyzed rebirth for the entire Pineywoods ecosystem.

Best Places to See Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in the Pineywoods

For the best RCW and Pineywoods wildlife viewing, consider these destinations:

National Forests:

- Sam Houston National Forest (RCW populations, trails, viewing platforms)

- Angelina, Davy Crockett, and Sabine National Forests (spotting RCWs, forest walks)

State Forests:

- W.G. Jones State Forest (Conroe): RCW colony clusters, boardwalks, education center

- I.D. Fairchild State Forest (Rusk-Palestine): rare plant viewing

Big Thicket National Preserve:

- Visitor center, 40+ miles of trails, paddling on the Neches River, diverse birdwatching, and accessible wildlife blinds.

State Parks:

- Caddo Lake (cypress sloughs), Village Creek, Martin Dies Jr. State Park

Pro Tips:

- Arrive at sunrise; listen for RCW “churr” calls.

- Locate resin wells on pine trunks—signature of active RCW territory.

- Use provided visitor maps for targeted wildlife hot spots.

Seasonal Visiting Guide

Spring brings RCW courtship, wildflower blooms, and a surge in migrant birds. Summer is lush, with morning activity peaks and pitcher plants in bloom—though heat and humidity demand early outings. Fall offers comfortable trails, a diversity of migrating birds, and magical forest lighting. Winter rewards visitors with visible eagle roosts, clear sightlines for RCW cavities, and crisp hiking conditions—making every season ideal for a Pineywoods adventure.

Planning Your Visit

Recommended base locations for Pineywoods nature tourism include Huntsville, Lufkin, and the Beaumont area. Gear up with binoculars, a camera with a telephoto lens, sturdy hiking boots, and insect repellent. The U.S. Forest Service and Big Thicket rangers offer guided walks and educational programs—ideal for first-timers. Whether you’re a seasoned birder or visiting for the first time, witnessing Red-cockaded Woodpeckers in their natural habitat restoration areas is an unforgettable wildlife conservation experience.

Remember, ethical wildlife photography means keeping distance from cavity trees and minimizing disturbance to foraging and nesting birds. Always follow posted signs and conservation ethics to ensure both personal safety and RCW success.

Getting Involved in Conservation

The Pineywoods community thrives on volunteer energy and public support. Opportunities abound to participate in forest restoration, species monitoring, and citizen science projects—just sign up through organizations like the Longleaf Alliance, Texas Master Naturalists, and national platforms such as eBird. Protecting Red-cockaded Woodpecker habitat and supporting endangered species recovery efforts helps ensure the long-term survival of this remarkable bird and the entire Pineywoods ecosystem.

Sharing personal observations and photos on iNaturalist directly supports scientific research and habitat management efforts, boosting statewide conservation outcomes.

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker: A Conservation Success Story

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker’s resurgence is more than just a bird’s story; it’s a Texas conservation victory with ecosystem-wide implications. Witnessing these birds thrive in the Pineywoods demonstrates that with collective resolve, endangered species can rebound and forgotten forests can recover.

Plan a visit this season to see RCWs in action or sign up for the Pineywoods Conservation newsletter for updates, viewing alerts, and downloadable wildlife maps. Share this success story with friends and on social media, adding momentum to Texas’s role as a leader in conservation. For those moved to action, direct links for volunteer signups, tour bookings, and donation options can be found throughout this site—each click furthers the cause.

Experience the Pineywoods renaissance—one woodpecker, one hike, one story at a time.