Texas Ecoregions: Complete Guide to All 10 Natural Regions

Introduction

From the towering peaks of the Guadalupe Mountains to the humid forests of East Texas, from the sweeping coastal marshes of the Gulf to the stark beauty of the Chihuahuan Desert, Texas contains an astonishing range of natural landscapes. This ecological diversity isn’t random—it’s the result of unique geography, climate patterns, and geological history that have shaped the state into 10 distinct natural regions, or ecoregions.

Understanding Texas ecoregions helps you appreciate the incredible biodiversity of the Lone Star State, whether you’re planning a native garden, seeking the best wildlife watching locations, or simply curious about the natural world around you. This complete guide to Texas’s 10 ecoregions will help you identify which natural region you live in, discover the unique plants and animals that call each area home, and plan unforgettable visits to some of the most spectacular landscapes in North America.

What Are Ecoregions?

Definition and Purpose

Ecoregions are large areas of land or water that share similar characteristics in terms of geography, climate, soils, vegetation types, and wildlife communities. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies these natural regions based on a combination of factors including geology, topography, climate patterns, soil composition, and dominant plant and animal species.

Think of ecoregions as nature’s neighborhoods—each one has its own personality, shaped by rainfall amounts, elevation, temperature ranges, and millions of years of geological processes. The Texas ecoregions system helps scientists, conservationists, and land managers understand and protect the state’s diverse ecosystems.

Why Ecoregions Matter

Understanding Texas natural regions serves several practical purposes:

- Conservation planning: Identifying endangered species and threatened habitats becomes more effective when we understand the unique characteristics of each ecological region. Conservation efforts can be tailored to the specific needs of each ecoregion.

- Native landscaping: Homeowners and landscapers can select plants adapted to their specific Texas ecoregion, resulting in gardens that thrive with less water, fewer chemicals, and minimal maintenance while supporting local wildlife.

- Understanding local ecosystems: Whether you’re an educator, student, or nature enthusiast, knowing your ecoregion helps you understand why certain plants and animals live in your area and how local ecosystems function.

- Wildlife management: Hunters, ranchers, and wildlife managers use ecoregion information to make informed decisions about habitat management, species conservation, and land stewardship.

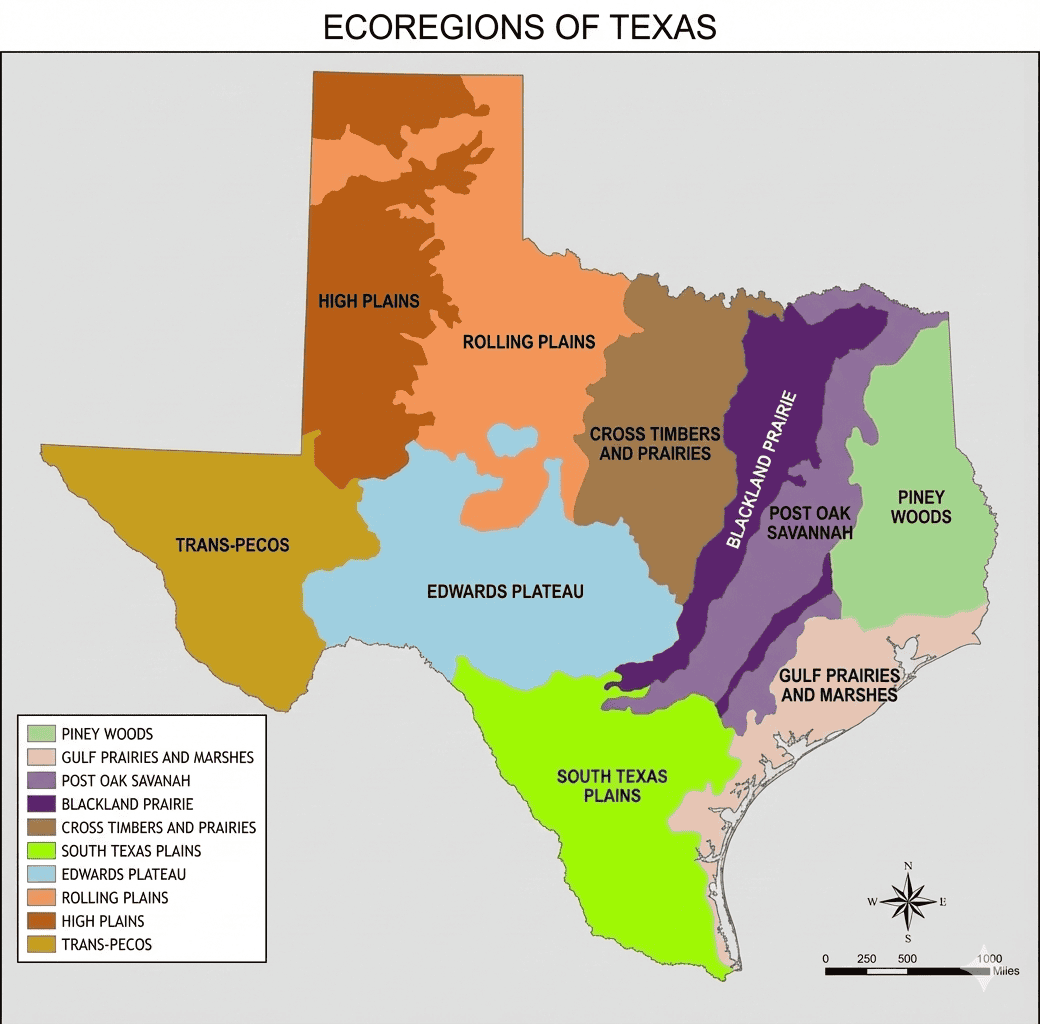

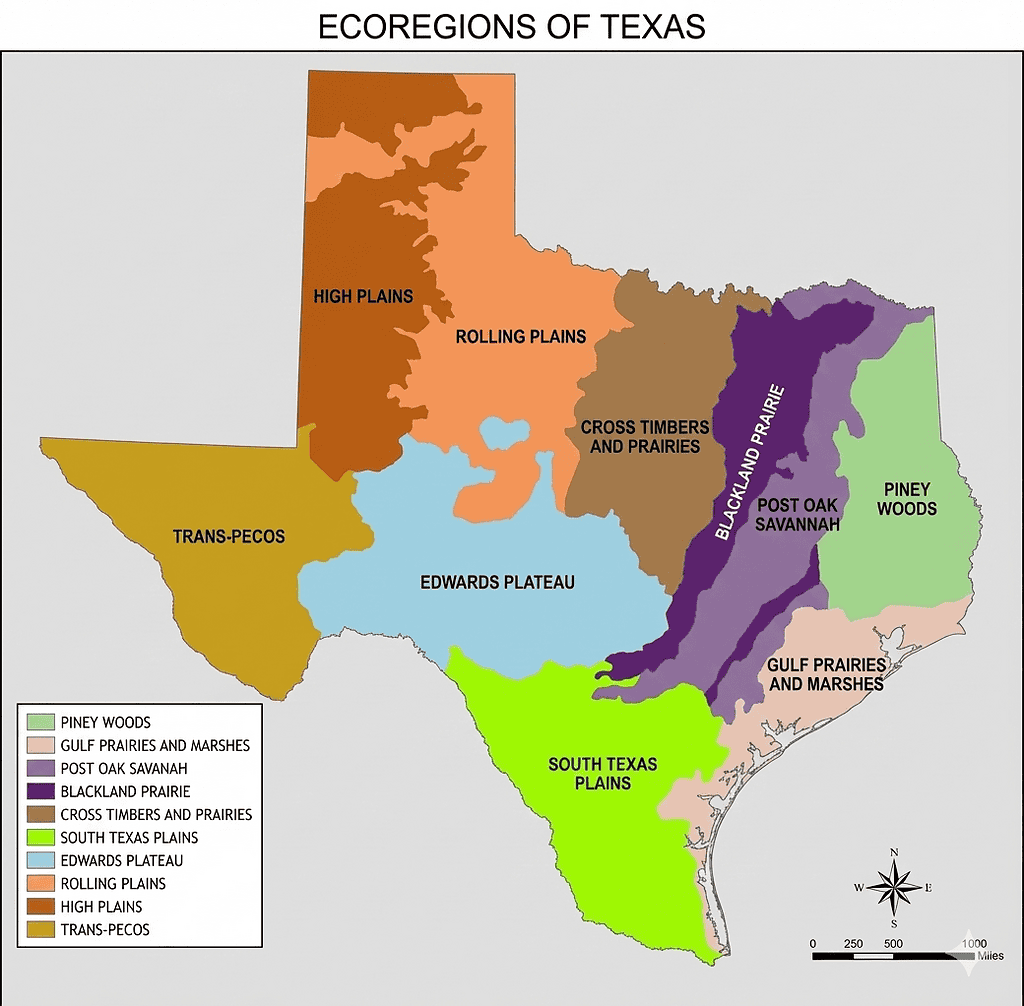

The 10 Ecoregions of Texas: Overview

Texas is unique among U.S. states in containing 10 distinctly different ecoregions within its borders—more ecological diversity than most countries possess. This remarkable variety results from the state’s enormous size (268,596 square miles), dramatic elevation changes from sea level to over 8,700 feet, and position at the convergence of multiple climate zones.

The 10 Natural Regions of Texas

- Piney Woods — Dense forests in the humid east

- Gulf Prairies and Marshes — Coastal ecosystems along the Gulf of Mexico

- Post Oak Savannah — Transitional woodlands and prairies

- Blackland Prairies — Fertile tallgrass prairies (mostly converted to agriculture)

- Cross Timbers — Oak forests interspersed with grasslands

- South Texas Plains — Subtropical thorn scrub region

- Edwards Plateau — The beloved Texas Hill Country

- Rolling Plains — Transitional prairies and mesquite grasslands

- High Plains — Flat, elevated panhandle region

- Trans-Pecos — Mountains and deserts of Far West Texas

Geographic Distribution Across Texas

The Texas ecoregions follow a general pattern from east to west, reflecting a dramatic rainfall gradient. The Piney Woods in the east receive 40–60 inches of annual rainfall, creating lush forests, while the Trans-Pecos region in far West Texas receives only 8–20 inches, resulting in desert landscapes.

Elevation also plays a crucial role in shaping these natural regions. From sea level along the Gulf Coast, the land gradually rises to the High Plains’ 3,000–4,000 foot elevation, then dramatically climbs to the Trans-Pecos mountains, where peaks exceed 8,700 feet.

This combination of rainfall gradients, elevation changes, soil types, and temperature variations creates the remarkable ecological diversity that makes Texas a biodiversity hotspot.

1. Piney Woods

Location and Geography

The Piney Woods ecoregion blankets the eastern edge of Texas, forming the state’s only true forested region. This lush landscape extends from the Louisiana border westward approximately 75–125 miles, covering all or parts of 43 counties including Harrison, Marion, Cass, Bowie, Cherokee, Angelina, Jasper, Newton, Tyler, and Polk counties. The region encompasses roughly 16 million acres of rolling, forested terrain.

Climate Characteristics

This is Texas’s wettest ecoregion, receiving 40–60 inches of annual rainfall distributed fairly evenly throughout the year. Summers are hot and humid with temperatures regularly exceeding 90°F, while winters are mild with occasional freezes. The growing season extends 240–290 days, supporting the lush vegetation that characterizes this region. High humidity year-round creates a climate more reminiscent of the Deep South than typical Texas landscapes.

Landscape and Terrain

Gently rolling hills covered in pine and hardwood forests define the Piney Woods terrain. Four distinct pine forest types exist here:

- Longleaf pine

- Shortleaf pine

- Loblolly pine

- Slash pine

The landscape is crisscrossed by numerous rivers, streams, bayous, and natural lakes—features rare elsewhere in Texas.

Sandy, acidic soils support the pine forests, while bottomlands along waterways contain rich, alluvial soils that support diverse hardwood communities. The terrain’s topography, though modest in elevation change, creates varied microclimates and habitats within the region.

Flora: What Grows Here

Towering loblolly pines, shortleaf pines, and the increasingly rare longleaf pines form the forest canopy. These coniferous species mix with hardwoods including sweetgum, southern red oak, water oak, hickory, and magnolia trees. In bottomland areas, bald cypress and tupelo create swampy forests draped with Spanish moss.

The understory supports yaupon holly, American beautyberry, possumhaw, and various azalea species. The forest floor bursts with wildflowers in spring, including trilliums, wild azaleas, and numerous fern species. Carnivorous plants like pitcher plants and sundews thrive in the region’s acidic bogs.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

The Piney Woods boasts the highest biodiversity of any Texas ecoregion. White-tailed deer browse through the forests, while wild hogs root in the underbrush. The endangered red-cockaded woodpecker depends on mature longleaf pine forests, its distinctive white cheek patches making it recognizable to careful observers.

American alligators inhabit rivers, bayous, and lakes—this is the western edge of their range. Bird diversity is exceptional, with wood ducks, pileated woodpeckers, prothonotary warblers, and dozens of other species filling the forests with song. Armadillos, raccoons, opossums, and bobcats are common mammals, while cottonmouth snakes and timber rattlesnakes represent important reptilian predators.

Best Places to Visit

- Caddo Lake State Park (bald cypress swamps and boat tours).

- Big Thicket National Preserve (diverse habitats; “biological crossroads of North America”).

- Davy Crockett National Forest (hiking, camping, wildlife observation).

- Tyler State Park (forest recreation and trails).

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (March–May): Wildflowers, migrating songbirds, comfortable hiking weather.

- Fall (October–November): Cooler temperatures and foliage changes.

- Summer: Hot, humid, heavy mosquitoes (still possible with preparation).

- Winter: Mild but can be rainy; good for waterfowl and fewer crowds.

Unique Features

The Piney Woods region is the only Texas ecoregion containing natural lakes (most Texas lakes are reservoirs). Caddo Lake, shared with Louisiana, is the state’s only natural lake of significant size.

This region supports the highest biodiversity in Texas and represents the western extension of the great southeastern pine forests. It’s the only true forest ecoregion in the state, dramatically different from all other Texas natural regions.

2. Gulf Prairies and Marshes

Location and Geography

The Gulf Prairies and Marshes ecoregion forms a narrow coastal strip stretching over 360 miles along the Texas Gulf Coast from the Louisiana border to Mexico. This region encompasses major cities including Houston, Galveston, Corpus Christi, and Brownsville, covering approximately 10 million acres. The landscape includes barrier islands, coastal prairies, and extensive saltwater and freshwater marshes.

Climate Characteristics

A humid subtropical climate dominates this coastal ecoregion, with high humidity year-round and 20–55 inches of annual rainfall varying from south to north.

Hurricane season (June–November) brings the constant threat of tropical storms and hurricanes, which significantly influence the region’s ecology. Salt spray from the Gulf affects vegetation near the coast, limiting which plants can survive the harsh conditions.

Winters are mild, rarely experiencing hard freezes, while summers are hot and humid with frequent afternoon thunderstorms. The moderating influence of Gulf waters keeps temperatures relatively stable compared to inland regions.

Landscape and Terrain

Flat to gently rolling coastal prairies transition into extensive marshlands as you approach the Gulf. The landscape features a complex system of bays, estuaries, tidal flats, and barrier islands. Elevations rarely exceed 150 feet, with much of the region near sea level.

Barrier islands like Padre Island and Galveston Island protect the mainland from direct wave action, while vast marshes behind them provide critical habitat for countless species.

Soil types range from sandy barrier island soils to organic-rich marsh soils and clay prairies.

Flora: What Grows Here

Coastal prairies historically supported tallgrass species like big bluestem, Indiangrass, and switchgrass, though most have been converted to agriculture or urban development. Coastal live oak trees form isolated groves called mottes on slight elevations in the prairie.

Marshlands support smooth cordgrass, saltgrass, black needlerush, and marshhay cordgrass in saltwater areas. Freshwater marshes contain cattails, bulrushes, and southern wild rice.

The barrier islands feature specialized sea oats, gulf croton, and other salt-tolerant plants that stabilize dunes. Mangroves appear near the Mexico border, representing the northern limit of these tropical plants.

After disturbance, huisache and honey mesquite quickly colonize prairie areas.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

This ecoregion is critically important for migratory birds following the Central Flyway. Millions of birds rest and refuel here during spring and fall migrations, making it one of the premier birding destinations in North America.

The endangered whooping crane winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge—one of the world’s rarest and most spectacular birds. Brown pelicans, once endangered but now recovered, patrol the coastline. Roseate spoonbills wade through shallow waters, their pink plumage brightening coastal marshes.

Five species of sea turtles visit Texas waters, with the critically endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtle nesting on Padre Island. American alligators inhabit freshwater marshes and bayous.

Coastal waters support redfish, speckled trout, flounder, and countless other species in productive estuary systems.

Best Places to Visit

- Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (winter home of the whooping crane; excellent wildlife viewing year-round).

- Padre Island National Seashore (longest undeveloped barrier island in the world; sea turtle nesting habitat).

- Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge (outstanding birding opportunities).

- Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge (marsh habitats and birding).

- Galveston Island State Park (beach access and coastal prairie restoration projects).

Best Time to Visit

- Spring migration (March–May): Millions of songbirds, shorebirds, and waterfowl move through the region.

- Fall migration (September–November): Another major migration wave with excellent birding.

- Winter (December–February): Ideal for whooping crane viewing and comfortable beach weather.

- Summer: Good for beach activities, but brings extreme heat, humidity, and jellyfish blooms.

Unique Features

This ecoregion serves as a critical stopover for migratory birds, with some locations recording over 400 bird species.

It’s the most endangered Texas ecoregion, with over 70% of coastal prairies converted to rice fields, urban development, or industrial use.

The productive estuaries support Texas’s vital commercial fishing and recreational fishing industries. This is Texas’s only coastal ecosystem, dramatically different from all inland ecoregions.

3. Post Oak Savannah

Location and Geography

The Post Oak Savannah forms a transitional belt between the humid Piney Woods to the east and the drier prairies to the west. This ecoregion arcs through central Texas from the Red River south to the San Antonio area, covering approximately 8.5 million acres across 38 counties. Major towns in this region include Bryan–College Station, Caldwell, Bastrop, and Smithville.

Climate Characteristics

The Post Oak Savannah receives 35–50 inches of annual rainfall, placing it between the wetter Piney Woods and drier prairie regions. Temperatures are moderate, with hot summers reaching the mid-90s°F and mild winters with occasional freezes. Humidity levels are high, though not as extreme as the Piney Woods. This climate creates ideal conditions for the mix of woodland and grassland that characterizes the region.

Landscape and Terrain

Gently rolling hills covered with a mosaic of oak woodlands and grasslands define this landscape. Sandy soils support the oak forests, while clay soils often contain prairie openings. The topography features low, rounded hills rarely exceeding 200 feet in elevation change, creating a park-like appearance in undisturbed areas.

Streams and rivers cut through the landscape, their bottomlands supporting denser forest cover. This varied terrain creates diverse habitats supporting both forest and prairie species.

Flora: What Grows Here

Post oak trees give this ecoregion its name, their distinctive cross-shaped leaves recognizable throughout the region. Blackjack oak commonly grows alongside post oaks, both species adapted to the sandy soils. Yaupon holly and rusty blackhaw viburnum form understory layers beneath the oaks.

Prairie openings support little bluestem, Indiangrass, and a rich diversity of wildflowers including Texas bluebonnets, Indian blanket, coreopsis, and black-eyed Susan. In bottomlands, American elm, cedar elm, and pecan trees thrive.

The famous Lost Pines of Bastrop represent an isolated population of loblolly pines far from the main Piney Woods region—a botanical mystery that adds unique character to the area.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

White-tailed deer are abundant, thriving in the mix of cover and food sources. Wild turkeys roost in oak trees and forage in open areas. Eastern bluebirds nest in cavities of dead trees, their bright blue plumage adding color to the landscape.

Bobwhite quail populations have declined but still exist in well-managed areas with proper habitat. Fox squirrels are common in oak woodlands, while nine-banded armadillos root through leaf litter. Red-tailed hawks and great horned owls hunt from oak tree perches.

Eastern box turtles slowly navigate the forest floor, and various tree frogs fill spring evenings with calls. The region supports species from both eastern forests and western prairies, creating unique faunal diversity.

Best Places to Visit

- Bastrop State Park (protects part of the Lost Pines; excellent hiking through pine-oak forest).

- Lake Somerville State Park (water recreation plus trails through typical Post Oak Savannah habitat).

- Palmetto State Park (unusual dwarf palmetto stand and the beautiful Ottine Swamp).

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (March–May): Ideal for wildflower viewing, with fields of bluebonnets and other blooms.

- Fall (October–November): Pleasant temperatures and subtle oak foliage changes.

- Summer: Hot and humid, but full access to lakes and swimming areas.

- Winter: Mild and good for wildlife observation without crowds.

Unique Features

The Lost Pines of Bastrop represent an ecological mystery—an isolated population of loblolly pines separated from the main Piney Woods by over 100 miles.

This ecoregion serves as a transitional ecosystem, containing species from both eastern forests and western prairies. Historic oak savannahs maintained by periodic wildfires once created park-like landscapes that early settlers described as beautiful and haunting.

4. Blackland Prairies

Location and Geography

The Blackland Prairies form a narrow strip of incredibly fertile land stretching 300 miles from the Red River near the Texas–Oklahoma border south to San Antonio. This ecoregion includes major metropolitan areas—Dallas–Fort Worth, Waco, Austin, and San Antonio—and covers approximately 12 million acres across 25 counties.

The region’s rich, dark clay soils have made it one of the most important agricultural areas in Texas, but this same fertility has led to extensive conversion, making the Blackland Prairies the most endangered Texas ecoregion.

Climate Characteristics

Annual rainfall ranges from 30–40 inches, adequate for both agriculture and native tallgrass prairie. The climate features hot summers with temperatures frequently exceeding 95°F and mild winters with occasional cold snaps and ice storms.

Spring brings severe thunderstorms and tornado activity, particularly in the northern portions of the region. The growing season extends 240–270 days, supporting both warm-season and cool-season plant species. Periodic droughts historically shaped the ecology, favoring deep-rooted prairie plants adapted to water stress.

Landscape and Terrain

The terrain is nearly level to gently rolling, featuring deep, dark, alkaline clay soils that turn sticky and impassable when wet but crack deeply when dry.

These vertisols—soils that shrink and swell with moisture changes—historically supported some of the most productive tallgrass prairie in North America. Before European settlement, the landscape was a sea of grass with only scattered trees along streams.

Today, most native prairie has been plowed for crops or developed for urban and suburban use. Remaining native prairie fragments are precious and increasingly protected.

Flora: What Grows Here

Historic vegetation consisted of tallgrass prairie dominated by:

- Big bluestem

- Little bluestem

- Indiangrass

- Switchgrass

Some species grew over six feet tall. These deep-rooted grasses thrived in the fertile soil and survived periodic droughts and fires.

A spectacular diversity of wildflowers painted the prairie through the growing season, including Texas bluebonnets, Indian paintbrush, purple coneflower, black-eyed Susan, Maximilian sunflower, and prairie verbena (among many others). Over 500 plant species historically grew in Blackland Prairie ecosystems.

Trees were sparse, limited mainly to cedar elm, American elm, hackberry, bur oak, and eastern cottonwood along creek bottoms. Where prairie remains, these species still represent the limited woody vegetation.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

The historic wildlife community included bison, prairie wolves (red wolves), and black bears—all now extirpated from the region.

Today’s wildlife consists of species adapted to fragmented habitats and human-dominated landscapes. White-tailed deer thrive in remaining woodlands and edge habitats. Coyotes have become common throughout the region, even in urban areas.

Grassland birds like dickcissels, eastern meadowlarks, and grasshopper sparrows persist in remaining prairie fragments, though populations have declined dramatically. American kestrels—North America’s smallest falcon—hunt over grasslands and field edges.

The Texas horned lizard, once common, has become threatened due to habitat loss and declining prey populations. Bobwhite quail populations have decreased significantly but still exist in well-managed areas. Scissor-tailed flycatchers are common summer residents, their aerial displays and long tail feathers making them easy to identify. Burrowing owls occasionally appear in suitable prairie dog colonies.

Best Places to Visit

- Lyndon B. Johnson National Grassland near Decatur (largest publicly accessible grassland habitat).

- Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge (protects prairie remnants along with forests and wetlands).

- Clymer Meadow Preserve near Greenville (one of the best remaining examples of virgin Blackland Prairie).

- Parkhill Prairie near Austin (prairie remnant access).

- Various Native Prairies Association of Texas preserves (often small and may require advance permission).

Best Time to Visit

- April: Peak time for wildflowers, especially bluebonnets and Indian paintbrush.

- Spring (March–May): Migrating birds and comfortable temperatures ideal for hiking.

- Fall (October–November): Cooler weather and golden grasses.

- Winter: Generally mild but can bring ice storms; good for quiet visits and appreciating prairie “stark beauty.”

Unique Features

The Blackland Prairies are the most endangered Texas ecoregion, with an estimated 97% of native prairie converted to cropland, pasture, or urban development. Less than 1% of virgin prairie remains, making any intact prairie fragment incredibly valuable for conservation and ecological research.

The region’s incredibly fertile soils—some of the richest agricultural soils in North America—ironically led to its ecological downfall. What was once a sea of grass is now a sea of cotton, wheat, and suburban development.

Historical accounts describe tallgrass prairie so thick that wagons struggled to pass through, and wildflower displays so spectacular they drew visitors from distant cities.

5. Cross Timbers

Location and Geography

The Cross Timbers ecoregion consists of two distinct strips—the Eastern Cross Timbers and Western Cross Timbers—running north–south through north-central Texas and extending into Oklahoma. This region covers approximately 7 million acres, forming a distinctive vegetative boundary that early settlers found challenging to penetrate.

The Eastern Cross Timbers stretch from the Red River south through the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex, while the Western Cross Timbers lie further west, separated by the Grand Prairie region. Major towns include Fort Worth, Denton, Weatherford, and Stephenville.

Climate Characteristics

Annual rainfall ranges from 28–40 inches, with higher amounts in the eastern portions and decreasing westward. The climate features hot, dry summers with temperatures often exceeding 100°F and cold winters that can bring ice storms and occasional snow.

This ecoregion represents a transition zone between humid eastern regions and semi-arid western areas. Periodic droughts and occasional wet cycles create variable conditions that favor adaptable vegetation. Strong winds, especially in spring, characterize the region’s weather patterns.

Landscape and Terrain

Rolling hills and sandstone outcrops create more topographic relief than surrounding prairies. The distinctive feature is dense belts of oak forest alternating with prairie openings, creating a mosaic of wooded and open habitats.

Sandstone rocks and gravelly soils support the oak-dominated woodlands. Early settlers found the dense oak thickets nearly impenetrable, describing them as tangled “cross timbers” that blocked westward passage. These oak forests formed a distinct vegetative boundary clearly visible even today on satellite imagery.

Flora: What Grows Here

Post oak and blackjack oak dominate the woody vegetation, forming dense thickets on sandier soils. These tough, drought-resistant oaks create closed-canopy forests in draws and on north-facing slopes.

Plateau live oak and Texas red oak also occur in rockier areas. Ashe juniper (commonly called cedar) has expanded dramatically since fire suppression, often forming dense stands where prairie or open oak woodlands once existed. Eastern redcedar and red juniper also inhabit the region.

Prairie openings support little bluestem, Indiangrass, sideoats grama, and numerous wildflower species including Texas bluebonnet, Mexican hat, and Indian blanket. American beautyberry and fragrant sumac provide understory color and wildlife food.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

White-tailed deer populations are high, thriving in the mix of cover and food sources. Nine-banded armadillos are ubiquitous, rooting through leaf litter for insects. Wild turkeys are common, with good habitat producing healthy populations.

The endangered golden-cheeked warbler nests in mature Ashe juniper woodlands, stripping bark to build its nest. This beautiful bird spends winters in Central America but breeds only in Texas. Black-capped vireos, also threatened, utilize shrubby habitats with low-growing vegetation.

Eastern fox squirrels and gray foxes inhabit wooded areas, while coyotes are widespread. Great horned owls and red-tailed hawks are common predators. Greater roadrunners dart across roads and through scrubby areas hunting insects and small reptiles.

Collared lizards sun themselves on sandstone outcrops, displaying spectacular coloration during breeding season. Texas spiny lizards scurry up oak tree trunks when disturbed.

Best Places to Visit

- Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge (over 3,600 acres; bison, trails, wildlife viewing).

- Dinosaur Valley State Park near Glen Rose (dinosaur tracks in the Paluxy River bed plus Cross Timbers scenery).

- Possum Kingdom State Park (water recreation surrounded by classic Cross Timbers landscape).

- Lake Mineral Wells State Park (camping and hiking through oak-juniper woodlands and prairie openings).

- Cleburne State Park (camping and hiking in typical Cross Timbers habitats).

Best Time to Visit

- Fall (October–November): Excellent weather and subtle oak foliage color changes.

- Spring (March–May): Comfortable temperatures, wildflowers, and opportunities to hear golden-cheeked warblers singing.

- Summer: Hot and dry, but manageable early and late in the day.

- Winter: Can be cold, but offers solitude and good wildlife observation when leaves are off deciduous trees.

Unique Features

The Cross Timbers formed a distinct vegetative boundary that early settlers and Native Americans recognized as a major landmark. Historic accounts describe the dense oak thickets as nearly impenetrable obstacles to westward travel.

The region’s name comes from these “cross timbers” that ran perpendicular to the general east–west travel routes. Fossil discoveries in this region—particularly dinosaur tracks at Dinosaur Valley State Park—add geological interest beyond the ecological features.

The mix of woodland and prairie creates excellent wildlife habitat and high biodiversity for a relatively small region.

6. South Texas Plains

Location and Geography

The South Texas Plains ecoregion covers the southern tip of Texas, extending from the Gulf Coast inland approximately 200 miles and running from Corpus Christi south to Mexico. This region encompasses roughly 21 million acres, making it one of Texas’s largest ecoregions.

Major cities include Laredo, McAllen, Harlingen, and Brownsville in the Rio Grande Valley.

Climate Characteristics

Rainfall varies from 16–35 inches annually, with higher amounts near the coast decreasing inland. The subtropical climate features hot, humid summers with temperatures regularly exceeding 100°F and mild winters that rarely experience freezing temperatures.

This frost-free or nearly frost-free climate allows tropical and subtropical plant species to thrive. Droughts are common and sometimes severe, shaping vegetation toward drought-tolerant, thorny species.

Hurricane remnants occasionally bring heavy rainfall, and late summer and fall can see tropical storm influences from the Gulf.

Landscape and Terrain

Flat to rolling plains characterize the topography, with elevations rarely exceeding a few hundred feet. Sandy and clay loam soils support the distinctive thorn scrub vegetation that dominates the region.

The landscape was historically more open, with scattered brush, but fire suppression and overgrazing have led to dense brush encroachment. The lower Rio Grande Valley contains some of the most fertile soils and the densest remaining brush habitat.

Shallow, temporary pools (resacas) in the valley provide important wetland habitat during wet periods.

Flora: What Grows Here

Thorny shrubs and small trees dominate the vegetation, creating sometimes impenetrable thickets. Honey mesquite is ubiquitous, its deep roots accessing water unavailable to other plants. Huisache produces spectacular displays of fragrant yellow flowers in late winter.

Prickly pear cactus grows in large stands, some varieties reaching tree-like proportions. Texas ebony, with its beautiful dark wood, produces fragrant flowers and provides important wildlife habitat. Retama (Jerusalem thorn) displays brilliant yellow blooms along roadsides and disturbed areas.

Granjeno, blackbrush acacia, and brasil form the diverse woody understory. Texas palmetto appears in moist areas, and Texas sabal palm reaches the northern limit of its range here.

Native grasses include seacoast bluestem, Arizona cottontop, and plains bristlegrass, though many areas have been invaded by non-native grasses.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

The South Texas Plains support exceptional wildlife diversity, particularly for birds and rare mammals. The critically endangered ocelot survives in small numbers in the densest brush areas, primarily in Cameron and Willacy counties.

The extremely rare jaguarundi, a small wild cat, may persist in remnant populations, though sightings are scarce.

Green jays, with their brilliant green and blue plumage, are common in parks and refuges—this is the only place in the United States to reliably see this tropical species. Great kiskadees call loudly from riverside vegetation. Plain chachalacas produce raucous dawn choruses in thorny thickets.

Javelinas (collared peccaries) travel in groups, feeding on prickly pear cactus and other vegetation. Nilgai antelope, introduced from India, have established wild populations and are now hunted as game animals.

White-tailed deer in South Texas are smaller than northern populations but occur at high densities on well-managed ranches.

Loggerhead shrikes impale prey on thorns, creating gruesome but fascinating pantries. Harris’s hawks hunt cooperatively in small groups—unusual behavior for raptors.

The region supports over 500 bird species due to its position at the convergence of temperate and tropical zones.

Best Places to Visit

- Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge (best place to search for ocelots; outstanding birding year-round).

- Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge (world-renowned birding; species found nowhere else in the U.S.).

- Bentsen–Rio Grande Valley State Park (excellent trails through native thorn scrub habitat).

- King Ranch (nature tours showcasing South Texas wildlife and habitats; reservations required).

- Estero Llano Grande State Park (wetlands + thorn scrub; exceptional birding opportunities).

Best Time to Visit

- Winter (December–February): Best weather; mild temperatures ideal for hiking and birding; winter brings waterfowl to wetlands.

- Spring migration (April–May): Spectacular birding as northern-bound migrants pass through.

- Summer: Extremely hot and humid, but dedicated birders still visit seeking tropical species.

- Fall (September–November): Southbound migrants and more comfortable temperatures.

Avoid the region during peak summer heat unless you’re acclimated to extreme temperatures.

Unique Features

The South Texas Plains host the highest bird diversity in the United States, with over 500 recorded species. This region is the only place in the U.S. where certain Mexican bird species regularly occur, making it a pilgrimage site for serious birders.

The ocelot population (fewer than 120 individuals) represents one of North America’s rarest large mammals. Conservation efforts focus on preserving and connecting remaining brush habitat to prevent extinction.

Sadly, this ecoregion has been heavily impacted by agriculture (particularly citrus groves and row crops), urban development, and border infrastructure. Only about 5% of original native habitat remains intact, making it one of the most endangered ecosystems in North America.

7. Edwards Plateau

Location and Geography

The Edwards Plateau—better known as the Texas Hill Country—extends across central Texas from roughly the Austin area west to San Angelo and south toward the Mexico border. This beloved region covers approximately 24 million acres (making it one of Texas’s largest ecoregions) across 38 counties, including Kerr, Gillespie, Kendall, Bandera, Real, and Edwards counties.

Towns like Fredericksburg, Kerrville, Boerne, and Wimberley have become popular tourist destinations showcasing the region’s natural beauty and charm.

Climate Characteristics

Rainfall varies dramatically across this large region, from about 35 inches annually in eastern sections near Austin to less than 15 inches in western portions near the Pecos River. This gradient creates varying habitats from lush eastern valleys to more arid western landscapes.

Temperatures are moderate compared to surrounding regions, with elevation providing some relief from summer heat. Flash flooding is a serious concern—steep slopes and shallow limestone soils shed water rapidly, causing streams to rise quickly after thunderstorms. Springs and creeks provide reliable water sources even during dry periods.

Landscape and Terrain

Rugged, scenic hills and canyons carved through limestone bedrock define the Edwards Plateau landscape. Elevations range from about 750 feet in valleys to over 3,000 feet on hilltops.

The underlying limestone creates distinctive features: steep bluffs, hidden caves, spring-fed streams with crystal-clear water, and rocky outcrops. The soil layer is often thin, with limestone bedrock visible on hilltops and slopes, while valleys contain deeper soils that support denser vegetation.

This karst topography (terrain formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks) creates the region’s characteristic features including caves, sinkholes, and underground streams.

Flora: What Grows Here

Ashe juniper (locally called cedar) dominates much of the landscape, forming dense stands on slopes and hilltops. While often viewed negatively for water consumption, juniper provides critical habitat for endangered bird species.

Plateau live oak, Texas oak, and Lacey oak create mixed woodlands in valleys and on favorable sites. Texas persimmon, agarita, and mountain laurel form the shrub layer, with mountain laurel producing spectacular purple flower clusters in early spring. Spanish oak, shin oak, and escarpment black cherry add diversity to the woody species composition.

Plateau grasslands support little bluestem, sideoats grama, Texas wintergrass, and numerous other species. Wildflower displays draw thousands of visitors each spring—Texas bluebonnets, Indian paintbrush, wine cups, greenthread, and pink evening primrose create stunning color combinations along roadsides and in meadows.

Bald cypress trees line spring-fed streams and rivers, their feathery foliage and distinctive “knees” creating picturesque scenes. Sycamores and cedar elms provide shade along waterways.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

The endangered golden-cheeked warbler breeds exclusively in central Texas, depending on mature Ashe juniper woodlands for nesting. The black-capped vireo, another endangered species, inhabits shrubby areas with low-growing vegetation. Conservation efforts for these species have driven significant habitat management in the region.

White-tailed deer reach some of their highest densities in Texas Hill Country, with many trophy bucks produced on managed ranches.

The Guadalupe bass (Texas’s state fish) swims in clear Hill Country streams; it’s the only bass species endemic to Texas.

Cave species add unique biodiversity, including several species of blind salamanders, cave-dwelling invertebrates, and Mexican free-tailed bats that emerge from caves in massive evening flights. Bracken Cave, near San Antonio, hosts the world’s largest bat colony (20 million bats).

Armadillos, raccoons, and gray foxes are common mammals. Turkey vultures and black vultures soar on thermals above the hills. Greater roadrunners dash across roads pursuing lizards and insects.

Best Places to Visit

- Enchanted Rock State Natural Area (massive pink granite dome rising 425 feet above the surrounding terrain; spectacular views and hiking).

- Lost Maples State Natural Area (famous for fall foliage; bigtooth maples create brilliant autumn color rare in Texas).

- Guadalupe River State Park (swimming in clear water; hiking through classic Hill Country terrain).

- Pedernales Falls State Park (tiered limestone waterfalls and excellent birding).

- Natural Bridge Caverns (underground tours showcasing the region’s karst geology).

- Longhorn Cavern State Park and Friedrich Wilderness Park (additional access to Edwards Plateau habitats).

The entire region is dotted with small towns, wineries, and scenic drives.

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (March–May): Peak season, with wildflowers reaching maximum display in April, comfortable temperatures, and golden-cheeked warblers returning from Central America (expect crowds at popular destinations).

- Fall (October–November): Pleasant weather, fewer crowds, and spectacular color at Lost Maples (peak typically late October to early November, though timing varies).

- Summer: Great for swimming in cold springs and rivers, though temperatures can be hot.

- Winter: Mild and often quiet, providing solitude at popular sites.

Unique Features

The Edwards Plateau is Texas’s most popular tourist destination, with the Hill Country attracting millions of visitors annually. The region’s scenic beauty—combined with wineries, small-town charm, and outdoor recreation—creates a major economic driver.

The Edwards Aquifer recharge zone occupies much of the eastern Plateau. Rainwater percolating through limestone recharges this critical aquifer that supplies water to San Antonio and numerous smaller communities.

Unique cave ecosystems support rare and endangered species found nowhere else on Earth. Fall foliage viewing at Lost Maples offers a rare Texas experience more commonly associated with New England.

The region’s combination of rugged beauty, clear streams, and diverse wildlife makes it one of Texas’s most treasured landscapes.

8. Rolling Plains

Location and Geography

The Rolling Plains ecoregion occupies north-central Texas, forming a transitional zone between the higher, flatter High Plains to the west and the more humid Cross Timbers to the east. This region covers approximately 24 million acres, extending from just west of Fort Worth to Abilene and north to the Red River.

Major towns include Abilene, Wichita Falls, Vernon, and Childress.

Climate Characteristics

Annual rainfall ranges from 20–30 inches, with higher amounts in eastern sections decreasing westward. This semi-arid climate features hot summers with temperatures regularly exceeding 100°F and cold winters that can bring significant snow and ice.

Strong winds are constant, particularly in spring, and occasional blizzards sweep through in winter. This region represents the transition from humid to arid climates—enough rainfall exists to support grasslands, but water stress shapes vegetation patterns. Periodic droughts can be severe and prolonged.

Landscape and Terrain

Gently rolling to hilly terrain characterizes this ecoregion, with erosion-carved canyons providing dramatic relief in some areas. Distinctive red soils and rock formations (the result of Permian “red beds”) give the landscape its characteristic rusty color.

Elevations range from 1,000 to 2,500 feet. The Caprock Escarpment—a dramatic erosional cliff—forms the eastern boundary between the Rolling Plains and the High Plains, with vertical drops of several hundred feet in places.

Rivers and streams have cut deep canyons into the plains, creating rugged landscapes that contrast with the generally open terrain.

Flora: What Grows Here

A mesquite–grassland mix dominates much of the region. Honey mesquite has expanded dramatically since fire suppression and overgrazing, often forming dense thickets where grasslands once prevailed. Catclaw acacia and lotebush add to the shrubby vegetation.

Native grasses include buffalograss, blue grama, sideoats grama, little bluestem, and sand dropseed—mostly short and mid-grass species adapted to lower rainfall.

Sand shinnery oak forms low-growing thickets on sandy soils. Scattered junipers (Eastern redcedar and Ashe juniper) and cottonwoods along waterways provide the limited tree cover.

Wildflowers include Indian blanket, purple prairie clover, winecup, and Texas bluebonnet in suitable areas.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

Mule deer replace white-tailed deer as the dominant cervid in western portions of this region, while both species occur in transitional areas.

Pronghorn antelope can be seen in open areas; they’re capable of running 60 mph (North America’s fastest land animal). Black-tailed prairie dogs form colonial towns where allowed to persist, and their burrow systems provide habitat for many associated species.

The greater prairie-chicken, once common, now persists in reduced numbers, with protected populations on private ranches and public lands.

Western diamondback rattlesnakes are among the region’s most impressive reptiles, sometimes reaching lengths over six feet. Texas horned lizards still occur in areas with good habitat and abundant harvester ant populations. Collared lizards show spectacular breeding colors on rocky outcrops.

Coyotes, badgers, swift foxes, and bobcats represent the carnivores. Burrowing owls nest in prairie dog burrows, while Mississippi kites perform graceful aerial displays. Scissor-tailed flycatchers are common in summer, and lark buntings and longspurs visit in winter.

Best Places to Visit

- Caprock Canyons State Park (stunning canyon scenery; home to the official Texas State Bison Herd; great hiking and wildlife viewing).

- Copper Breaks State Park near Quanah (classic Rolling Plains landscapes with rugged canyons and copper-colored rock formations).

- Big Spring State Park (views over the surrounding plains).

- Wildlife Management Areas (public hunting and wildlife observation opportunities).

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (March–May): Wildflowers, comfortable temperatures, and migrating birds.

- Fall (September–November): Pleasant weather, especially October when temperatures moderate and skies turn brilliantly clear.

- Winter: Can be harsh (cold winds, snow, and ice) but offers solitude and unique winter bird viewing.

- Summer: Hot and can be uncomfortable, though early morning and evening visits are manageable.

Strong winds are common year-round but particularly noticeable in spring.

Unique Features

The Texas State Bison Herd at Caprock Canyons represents a remarkable conservation success, with bison returned to landscapes they historically dominated. Watching these massive animals move across canyon grasslands evokes images of the historic Great Plains.

Prairie dog towns (where they still exist) provide fascinating wildlife viewing. These keystone colonies support entire ecosystems, with burrowing owls, swift foxes, ferruginous hawks, and numerous other species depending on prairie dog communities.

The region’s oil and gas production has shaped its economy and landscape for over a century, with pump jacks dotting the horizon.

The Rolling Plains are a true transition zone between humid and arid Texas, supporting species from both eastern and western faunal groups.

9. High Plains

Location and Geography

The High Plains ecoregion occupies the Texas Panhandle, forming part of the Great Plains that extend from Canada to Mexico. This distinctive flat, elevated plateau covers approximately 19 million acres in the northernmost part of Texas.

Major cities include Amarillo, Lubbock, Plainview, and Dalhart. The High Plains are sometimes called the Llano Estacado (“Staked Plains”), a name with disputed origins but possibly referring to the flat terrain or stakes early explorers used for navigation.

Climate Characteristics

This semi-arid region receives 15–21 inches of annual rainfall, with most precipitation falling during the warm season as intense thunderstorms. The climate features extreme temperature swings—summer highs exceeding 100°F contrast with winter lows well below freezing.

Blizzards can strike with little warning, and ice storms occasionally paralyze the region. Strong winds are nearly constant, historically driving windmills that pump groundwater and, more recently, turning massive wind turbines generating electricity.

The combination of low rainfall, strong winds, and extreme temperatures creates harsh conditions that limit plant and animal diversity.

Landscape and Terrain

The High Plains present some of the flattest terrain in North America, with gentle slopes of less than one degree over miles. This nearly level surface sits at elevations of 3,000–4,500 feet, making it one of Texas’s highest regions despite lacking visible relief.

Playa lakes—shallow, seasonal wetlands—dot the landscape, filling with water after heavy rains then drying out completely during droughts. These unique ephemeral wetlands provide critical habitat for migratory waterfowl and shorebirds, though many playas have been filled or degraded by agricultural practices.

At the edges of the High Plains, erosion has created dramatic canyons. Palo Duro Canyon, carved by the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River, drops 800 feet below the surrounding plateau, creating spectacular red-rock scenery.

Flora: What Grows Here

Short-grass prairie dominates the natural vegetation. Buffalograss and blue grama form the characteristic short turf that historically supported massive bison herds. Western wheatgrass, sideoats grama, and hairy grama add diversity to grasslands.

Yucca plants, with their sword-shaped leaves and tall flower stalks, dot the prairie. Prickly pear cactus grows in rocky areas and on less productive soils. Along the few streams, cottonwoods and willows provide the only significant tree cover in the natural landscape.

Most of the High Plains have been converted to agriculture. Wheat, cotton, corn, and sorghum fields now dominate, irrigated by groundwater from the Ogallala Aquifer. In Palo Duro Canyon and similar protected areas, junipers cling to canyon walls, and diverse plant communities thrive in the varied microhabitats.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

Pronghorn antelope are the iconic High Plains mammal, their tan and white coloring visible from great distances across open country. These fast animals evolved to outrun extinct American cheetahs and can still reach speeds of 60 mph.

The lesser prairie-chicken (a threatened species) performs spectacular courtship displays on traditional breeding grounds called leks. Conservation efforts aim to preserve remaining grassland habitat for these declining birds.

Swift foxes (North America’s smallest wild dog) hunt across the plains at night. Burrowing owls nest in abandoned badger or prairie dog burrows. Mountain plovers breed on short-grass prairies, preferring areas with minimal vegetation.

Playa lakes attract massive numbers of migrating waterfowl (mallards, northern pintails, green-winged teal, and northern shovelers) by the thousands. Sandhill cranes stop during migration, their ancient calls filling the air.

Western diamondback rattlesnakes, ornate box turtles, and various lizard species represent the reptiles. Black-tailed jackrabbits are common, their enormous ears helping dissipate heat.

Best Places to Visit

- Palo Duro Canyon State Park (the “crown jewel”; about 30 miles of trails, camping, horseback riding, mountain biking; the outdoor musical TEXAS performs in summer).

- Buffalo Lake National Wildlife Refuge (playa lake habitat and grasslands; excellent birding during migration).

- Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument (ancient quarries where Native Americans mined high-quality flint).

- Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon (excellent context for the area’s natural and cultural history).

- Amarillo (common gateway city for exploring the region).

Best Time to Visit

- Spring (April–May): Wildflowers in the canyons, comfortable temperatures, and prairie-chicken courtship displays.

- Fall (September–October): Pleasant weather, autumn color in canyon vegetation, and waterfowl migration.

- Summer: Hot but manageable in canyons where shade exists; the outdoor musical at Palo Duro Canyon runs June–August.

- Winter: Can be harsh (blizzards, ice storms, bitter cold), but snow-covered landscapes and winter birds can be spectacular.

Always check weather forecasts and road conditions before visiting in winter.

Unique Features

Palo Duro Canyon—the second-largest canyon in the United States—provides dramatic scenery unexpected in the flat Panhandle. The colorful rock layers reveal geologic history spanning millions of years.

The High Plains are the wind energy capital of Texas and one of the world’s premier wind power regions, with massive wind farms visible across the landscape.

The Ogallala Aquifer, underlying the High Plains, made large-scale irrigation agriculture possible but is being depleted faster than it recharges. Water conservation remains a critical issue for the region’s future.

Playa lake ecosystems are uniquely important: temporary wetlands that support surprising biodiversity despite harsh conditions and provide critical habitat to millions of migratory birds using the Central Flyway.

10. Trans-Pecos

Location and Geography

The Trans-Pecos—literally “across the Pecos River”—occupies far West Texas, covering approximately 18 million acres across 12 counties. This is Texas’s most remote, rugged, and geologically diverse region.

Major towns include El Paso, Alpine, Marfa, Fort Davis, and Terlingua, though much of the region remains essentially unpopulated wilderness. The Trans-Pecos is Texas’s largest ecoregion by area despite relatively low population density.

It contains true mountains, authentic desert landscapes, and some of the most spectacular scenery in North America.

Climate Characteristics

This is Texas’s driest ecoregion, receiving 8–20 inches of annual rainfall depending on elevation and location. Desert basins may receive less than 10 inches annually, while mountains can receive 20 inches or more.

The climate is arid to semi-arid with low humidity and abundant sunshine (over 300 sunny days per year in many areas). Temperature variations are extreme: summer days regularly exceed 100°F in lowlands, while winter nights can drop well below freezing.

Mountain locations moderate temperatures somewhat, with elevations above 6,000 feet offering relief from desert heat. The combination of clear skies and low humidity creates dramatic daily temperature swings—80°F daytime temperatures may drop to 40°F at night.

Landscape and Terrain

Dramatic mountains, including Texas’s highest peaks, define much of the Trans-Pecos landscape. Guadalupe Peak reaches 8,751 feet—the highest point in Texas.

The Chisos Mountains rise like an island from the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert, creating unique “sky island” habitats. The Chihuahuan Desert dominates lower elevations, characterized by basin-and-range topography: elongated mountains separated by broad desert valleys.

Volcanic rock formations create otherworldly landscapes in places. Ancient lava flows, extinct volcanoes, and colorful rock layers add geological interest.

Canyons carved by the Rio Grande—particularly Santa Elena Canyon, Mariscal Canyon, and Boquillas Canyon in Big Bend—feature sheer limestone walls rising 1,500 feet above the river. Dry lake beds (playas) and rocky badlands add to the landscape diversity.

Flora: What Grows Here

Desert plants dominate lower elevations. Creosote bush, with its distinctive aroma after rain, blankets vast areas. Lechuguilla (a large agave) is diagnostic of the Chihuahuan Desert.

Ocotillo produces spectacular red blooms on spindly stems that appear dead most of the year. Numerous cactus species thrive here, including prickly pear, cholla, horse crippler, and claret cup.

Sotol, yucca, and cenizo (Texas sage) add to desert plant diversity. After rare heavy rains, desert wildflowers can carpet the landscape in spectacular displays.

In mountains, vegetation changes with elevation. Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir grow at the highest elevations—the only place these species occur in Texas. Pinyon pine and alligator juniper inhabit middle elevations. Arizona cypress and Emory oak grow in protected canyons.

Cottonwoods and willows line water courses, their green foliage standing out dramatically against surrounding desert. Desert willow, despite its name, produces beautiful trumpet-shaped flowers.

Fauna: Wildlife You’ll Encounter

Large mammals have returned to the Trans-Pecos after near-extirpation. Mountain lions stalk remote canyons and mountains; the region supports one of Texas’s healthiest populations.

Mule deer browse desert vegetation, while desert bighorn sheep cling to steep mountain slopes (reintroduced after being hunted to local extinction). Mexican black bears have naturally recolonized the region after decades of absence, with Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend supporting growing populations.

Javelinas travel in groups through desert scrub. Pronghorn antelope inhabit desert grasslands in scattered herds.

Bird diversity is exceptional—over 450 species have been recorded in Big Bend National Park alone. Colima warblers breed only in the Chisos Mountains within the United States, making Big Bend a pilgrimage site for birders. Lucifer hummingbirds visit desert wildflowers.

Roadrunners, scaled quail, and Gambel’s quail are common desert birds. Western diamondback rattlesnakes, black-tailed rattlesnakes, and Trans-Pecos copperheads represent the region’s venomous snakes. Greater earless lizards, collared lizards, and Texas horned lizards bask on rocks.

The Big Bend slider turtle is found only in the Rio Grande and tributaries within Big Bend.

Best Places to Visit

- Big Bend National Park (801,163 acres of mountains, desert, and river canyons; key areas include the Chisos Basin, Santa Elena Canyon, Hot Springs, and the Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive).

- Guadalupe Mountains National Park (Texas’s highest peaks; the Guadalupe Peak summit trail; McKittrick Canyon for one of Texas’s best fall color displays).

- Davis Mountains State Park and Fort Davis National Historic Site (mid-elevation mountain scenery plus pioneer history).

- McDonald Observatory (public star parties and telescope viewing; the region’s dark skies make it one of the world’s premier astronomical research sites).

- Balmorhea State Park (massive spring-fed pool—1.75 acres—holding a constant 72–76°F year-round; supports endemic fish and offers desert-oasis swimming).

- Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site (near El Paso; ancient pictographs and world-class rock climbing; some areas require reservations and guided tours).

Best Time to Visit

Fall (October–November), winter (December–February), and spring (March–May) provide the best conditions for desert exploration. Temperatures are comfortable, though nights can be cold.

Spring can bring desert wildflower blooms in good rainfall years. Summer in desert basins is extremely hot (often over 110°F), but higher elevations remain pleasant.

Summer monsoons (July–August) bring afternoon thunderstorms and brief but intense rainfall that can cause flash flooding. The high mountains are accessible year-round, with winter occasionally bringing snow.

Unique Features

The Trans-Pecos is Texas’s most remote region, with vast areas containing no paved roads or permanent settlements. This remoteness protects wilderness values increasingly rare in modern America.

Dark skies largely unaffected by light pollution make this one of the best stargazing regions in North America. McDonald Observatory and Big Bend National Park host astronomy programs that take advantage of these pristine night skies.

This is the only true desert in Texas (the Chihuahuan Desert) and the only region with true mountains reaching alpine and subalpine life zones.

The dramatic landscapes—sheer canyon walls, colorful rock formations, stark desert vistas, and mountain forests—create photographic opportunities unmatched elsewhere in Texas. The low population density also means wildlife thrives in ways impossible in more developed regions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How many ecoregions does Texas have?

The answer depends on the classification system used. The EPA Level III classification recognizes 10 ecoregions in Texas, which this guide follows. More detailed Level IV classifications divide Texas into dozens of sub-ecoregions based on finer-scale differences in geology, soils, vegetation, and land use.

What is the most biodiverse ecoregion in Texas?

Two Texas ecoregions compete for this distinction depending on how you measure biodiversity:

- Piney Woods: Often considered the highest overall species diversity due to abundant rainfall, varied habitats, and its position at the convergence of multiple ecological zones. This region supports more tree species, amphibians, and overall plant diversity than any other Texas ecoregion.

- South Texas Plains: Has the highest bird diversity in the United States (over 500 recorded species) because it sits at the convergence of temperate and tropical zones where Mexican species reach their northern limits, and it supports rare mammals like ocelots and jaguarundis found nowhere else in the country.

Which Texas ecoregion gets the most rainfall?

The Piney Woods is Texas’s wettest ecoregion, receiving 40–60 inches of annual rainfall distributed fairly evenly throughout the year. The eastern portions near Louisiana receive the highest amounts, supporting dense pine and hardwood forests.

What ecoregion is the Texas Hill Country?

The Texas Hill Country is the popular name for the Edwards Plateau ecoregion. This scenic region of limestone hills, clear streams, and spring wildflowers extends from the Austin area west to San Angelo and south toward the Mexico border.

Which ecoregion has the highest elevation?

The Trans-Pecos contains Texas’s highest elevations, with Guadalupe Peak reaching 8,751 feet (the highest point in the state). This far West Texas region includes true mountains with multiple peaks exceeding 8,000 feet and “sky island” habitats with species found nowhere else in Texas.

What is the driest ecoregion in Texas?

The Trans-Pecos is Texas’s driest ecoregion, receiving only 8–20 inches of annual rainfall depending on location and elevation. Desert basins may receive less than 10 inches annually, creating true Chihuahuan Desert conditions.

Which ecoregion is most endangered?

The Blackland Prairies are Texas’s most endangered ecoregion, with an estimated 97% of native prairie converted to cropland, pasture, or urban development. Less than 1% of virgin Blackland Prairie remains, scattered in small, isolated fragments.

The Gulf Prairies and Marshes are also severely endangered, with over 70% of coastal prairies converted to rice agriculture, urban development, or industrial use. The South Texas Plains have lost approximately 95% of native brush habitat to agriculture and development.

Can you see all 10 ecoregions in one trip?

Seeing all 10 Texas ecoregions in a single trip is theoretically possible but requires extensive driving (at least 2,000 miles) and leaves little time for enjoying each region.

A practical alternative is a 14-day tour that touches all 10 ecoregions:

- Days 1–2: Piney Woods (Big Thicket, Caddo Lake)

- Day 3: Post Oak Savannah (Bastrop / Lost Pines)

- Day 4: Gulf Prairies and Marshes (coastal areas)

- Day 5: South Texas Plains (Laguna Atascosa)

- Days 6–7: Edwards Plateau (Hill Country highlights)

- Day 8: Blackland Prairies (prairie remnants near Austin/Dallas)

- Day 9: Cross Timbers (Fort Worth area)

- Day 10: Rolling Plains (Caprock Canyons)

- Day 11: High Plains (Palo Duro Canyon)

- Days 12–14: Trans-Pecos (Big Bend)

A better approach is “regional sampler” trips (3–4 neighboring ecoregions per trip) to spend meaningful time in each.

How to use this guide

For native landscaping

Selecting plants native to your specific Texas ecoregion creates gardens that thrive with minimal inputs. Native plants are adapted to local rainfall, soil types, and temperature extremes—often requiring less water, fertilizer, and pest control than non-native species.

Basic approach:

- Identify which ecoregion you live in.

- Choose plants from your ecoregion’s flora (not from a very different region).

- Use local resources like county Extension offices or the Native Plant Society of Texas for recommendations and nursery sources.

For outdoor recreation

Texas’s diverse ecoregions offer year-round outdoor activities across very different landscapes. Consider visiting multiple ecoregions over time to experience the state’s full range—from kayaking through Piney Woods bayous to hiking Trans-Pecos mountains.

Safety considerations (quick)

- Heat and hydration: Texas heat can be dangerous. Carry plenty of water in warm months and start hikes early.

- Venomous wildlife: Rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths, and coral snakes occur in Texas—watch where you step and place your hands.

- Flash flooding: Never cross flooded roads or streams (“Turn around, don’t drown”). Hill Country and canyon terrain are especially prone to rapid flooding.

- Remote preparation: In remote regions (especially the Trans-Pecos), services and cell coverage are limited—carry emergency supplies and tell someone your plans.

Conclusion

Texas’s 10 ecoregions represent an extraordinary concentration of ecological diversity. Understanding your local ecoregion helps explain why certain plants and animals live where they do, supports better native landscaping choices, and makes it easier to explore Texas’s natural heritage with intent.

Each region deserves protection and stewardship so future generations can experience the landscapes that make Texas unique.